The promotion of false binaries has led to many moral, creative and political questions being perverted into simple “yes” or “no” statements. YIMBY vs. NIMBY, Monsanto vs. Raw Milk, or Car Culture vs. Bugman Fifteen Minute Cities are all false binaries where citizens who are seeking better lives and the truth are getting funneled into one compromised, controlled extreme or another.

I recently had the great honor of giving a presentation to the

Rising Tide Foundation that tracked the development of science, art and American history from the days of Alexander Humboldt, Thomas Cole and Charles Darwin all the way to the present. You can watch it here:

This essay is an expansion on the need for Americans to develop the sophistication needed to see past false binaries.

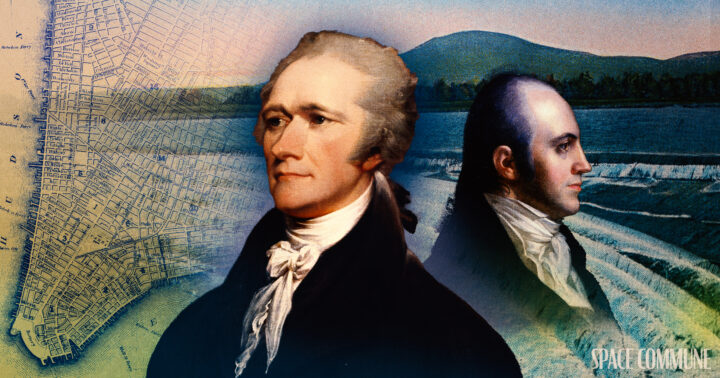

The first American school of art, the Hudson River School, was driven by patriots who wanted to find a way to get Americans to see past false binaries in a vulnerable time rife with direct and indirect British subversion. Artists like Thomas Cole, Asher Durand, Frederic Church and Albert Bierstadt strove to infuse an appreciation for the sublime into America’s unprecedented nation-building experiment. That’s why Thomas Cole’s Course of Empire series is the most prominent work in the Hudson River School’s body of work; as

Fox Green recently posited on American Thesis, it was a latent warning to the American people.

Conservation vs. Preservation

One of the most damaging false binaries to the development our country has been the debate between Preservation and Conservation.

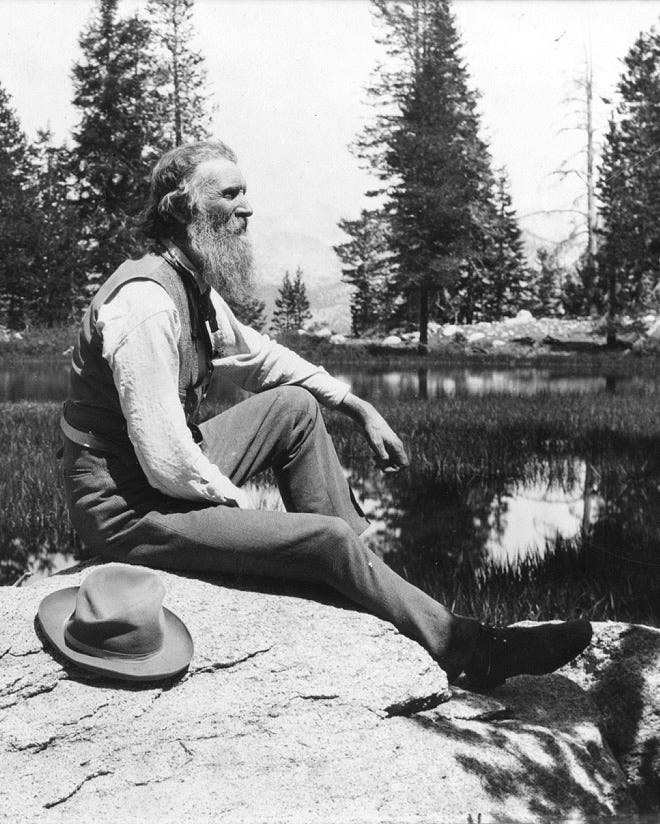

Preservation is John Muir, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Burroughs, and Henry David Thoreau’s continuation of the John Ruskin Pre-Raphaelite school of thought, rooted in a fear that industrialization was too disruptive to the existing order of feudalism. The preservation movement evolved out of the school of transcendentalism, which advocated for regressing to a natural, primitive state where Darwinian survival of the fittest can take its course unfettered.

The ethos of preservation can be seen today in the mystical worldviews of climate activism and “degrowth” zealotry.

In the the early 1900s, Theodore Roosevelt and his forestry minion Gifford Pinchot advocated for Conservation as a “smart use” alternative to Preservation. Conservation was a means to creating monopolies for logging and mining companies; using public-private partnerships to allow certain amounts of resource extraction while shutting out smaller market players from tapping into the commons. Conservation was built on Jeremy Bentham’s principle of utilitarianism; “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” would be achieved through doling out a small amount of depleting resources in an entropic world.

50 years before the Club of Rome’s loathsome Limits to Growth report, Pinchot even proposed a sort of global system of entropic control that would prevent sovereign nation-states to develop as they see fit:

“The conservation of natural resources is the key to the future. It is the key to the safety and prosperity of the American people, and all the people of the world, for all time to come. The very existence of our Nation, and of all the rest, depends on conserving the resources which are the foundation of its life. That is why Conservation is the greatest material question of all. … Moreover, Conservation is a foundation of permanent peace among the nations.”

Today, the utilitarianism of preservation lives on in the pragmatism of eco-modernism. As we wrote last year, a great example of this lies in nuclear energy; as our Great Reset, AI takeover of everything progresses, formerly anti-nuclear environmentalists are suddenly flipping to pro-nuclear simply because it’s the only pragmatic carbonless way to power the needed data centers. The notion of using nuclear energy to raise human flourishing is still dead and buried.

Did you know Space Commune is on Telegram? Join our channel and never miss an update!

The Utilitarian Battle over the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir

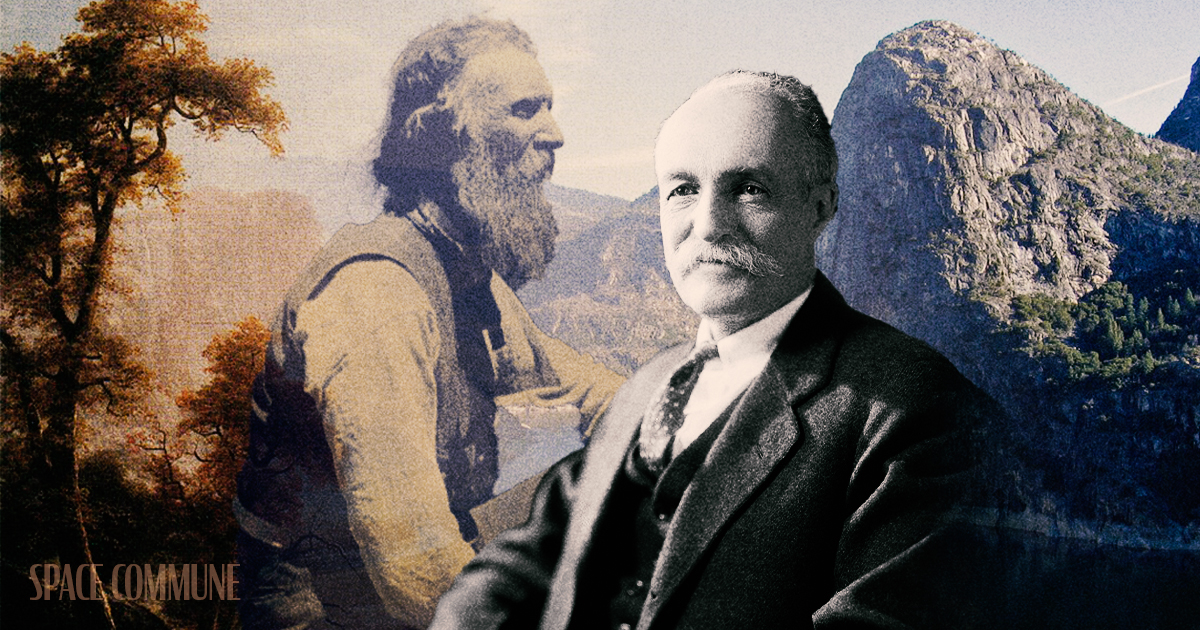

The battle between preservation and utilitarian conservation most famously played out in the years-long debate over San Francisco’s Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. Former colleagues John Muir (who founded the Sierra Club) and Gifford Pinchot duked it out in public as San Francisco’s desperate need for water to support a growing population hung in the balance:

In 1908, Theodore Roosevelt’s Department of the Interior granted San Francisco the authority to dam the Tuolumne River in Hetch Hetchy Valley for use as a reservoir. For Pinchot, a close friend and adviser to the president, this was an obvious choice. San Francisco’s water system could not adequately serve its growing population, and the dam presented a solution. For Muir, damming Hetch Hetchy was a blasphemy. You might as well deface the world’s great cathedrals, he said, “for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.” The issue was decided in December 1913, when Woodrow Wilson signed the Raker Bill into law, authorizing the dam’s construction. Muir would die just over a year later, and many would define Hetch Hetchy as the tragic climax of his life.

–Frenemies John Muir and Gifford Pinchot, National Endowment for the Humanities

Hetch Hetchy Reservoir stands as a monument to the false binary that was presented in the early 1900s. While water was a critical need to support a growing population, the long-term cost to the utilitarian taking of the Hetch Hetchy Valley (beautiful enough to be the subject of multiple Albert Bierstadt paintings) was very great. To this day, Malthusian preservationists like Patagonia’s Yvon Chouinard want to turn back the clock on the reservoir with the Restore Hetch Hetchy movement. If San Francisco’s water solution was beautiful and sublime, it would not be so vulnerable to attack from preservationists. Later in this essay, we’ll explore some positive examples of how development can infused with the sublimity of the Hudson River School.

The Hudson River School Connection

So what does this all have to do with the Hudson River School?

A great historical irony is that the Pinchot family—yes, the same Pinchots as Gifford Pinchot; are single-handedly responsible for the hoarding of and eventual destruction of a large cache of Hudson River School masterpieces. Instead of allowing the nation’s citizens to glimpse these works of genuine sublimity, Gifford’s father James Pinchot quietly entombed them in his own basement, ensuring that America’s cultural memory would be warped and contorted by the suffocating ideologies of “conservation” vs. “preservation.”

As Pierre Beaudry wrote in his masterful essay The Hudson River School, The Sleeping Giant of an American Renaissance, the lumber millionaire Pinchot actually bought Sanford Gifford’s Hunter Mountain, Twilight, and put it up over his family fireplace, as an ominous reminder of how public opinion was turning against their family business. Pinchot went on to befriend several Hudson River School painters and became their chief patrons:

Hunter Mountain was the first ecological scandal of deforestation in America to be put on record, and the man responsible for this state of affair was the most important ‘friend” of the Hudson River School: robber baron, James Pinchot, the New York City lumbering millionaire who befriended Whittredge and Gifford for his own financial benefit. However, this ecological deforestation was used to cover up a more sinister disaster: the “twilight” of the Hudson River School itself.

It was James W. Pinchot who bought Hunter Mountain, Twilight, and put it up as a mantelpiece over his family home fireplace, in order to hide it from the general public and use it as a Damocles’ sword over the head of his own son, warning him against the dangers of public opinion. Pinchot had baptized his son “Gifford” after the artist who painted that ominous truth, and even went as far as making Sanford Gifford his godfather. The picture was first exhibited at the National Academy of Design, and was later chosen to be exhibited at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1867. The painting was a smashing success and soon became the talk of all art lovers.

Moreover, since slashing and burning the American forests was not going to be very popular with public opinion, Pinchot resolved to create the Yale University School of Forestry. A fox would not have been more careful inside of the Hudson River chicken coop? Pinchot’s son, Gifford, was born in 1865, the same year that Gifford the artist began making sketches for this damning painting. Gifford Pinchot grew up to become the most notorious environmentalist friend of Theodore Roosevelt, and later became Governor of Pennsylvania for two terms. It was quite an irony that, in collusion with the kooky grand daddy of environmentalism, John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, was to become the first director of the United States Forest Service under the Roosevelt presidency, and the most prominent conservationist in America. Pinchot was the controller of slash and burn as well as conservation. So, Hunter Mountain, Twilight was a hidden “smoking gun” until the painting was retrieved after the death of Gifford Pinchot in 1946, and was exposed in Chicago’s Terra Museum of American Art where it now hangs.

According to an investigative reporter, Jim Lane, over 200 works of the Hudson River School had disappeared at the personal hands of James Pinchot, just like Hunter Mountain, Twilight did, and were found hidden, 90 years later, in the basement of the Pinchot residence. However, those paintings did not enjoy the same recovery, as did Gifford’s Hunter Mountain, Twilight. Lane reported the truth of what happened to those 200 paintings. He wrote: “Pinchot family members believe they may have simply been left there in the basement of the house were they were stored and been bulldozed over when the structure was demolished and the area reforested. Today, such nineteenth century Hudson River School paintings bring five and six figure bids at auction. Thus, in the greatest irony of all, valuable art was likely sacrificed in the name of conservation.”

What is the alternative to Conservation vs. Preservation?

Brutalist utilitarianism reached its nadir in the United States in the 1950s and 60s, as the nation became criss-crossed with transformers, power lines and looming nuclear plants. Development that is lacking in taste and sophistication inevitably creates fertile grounds for backlash, which made the LSD-fueled hippie uprising of the Esalen Human Potential Movement such a potent adversary to nuclear energy.

The true antidote the false dichotomy of conservation vs. preservation is to make the environment even more beautiful through development.

Albert Bierstadt, the artist behind the definitive painting of the Hetch Hetchy Valley, once expressed the hope that in another one of painting’s foreground plain, “a city, populated by our descendants, may rise, and in its art galleries this picture may eventually find a resting place.”

In his Essay on American Scenery, Thomas Cole wrote:

On the margin of that gentle river, the village girls may ramble unmolested, and the glad schoolboy with hook and line may pass his bright holiday. Those neat dwellings, unpretending to magnificence, are the abodes of plenty, virtue, and refinement.

In looking over the yet uncultivated scene, the mind’s eye may see far into future maturity. Where the wolf roams, the plow shall glisten; on the gray crag shall rise temple and tower. Mighty deeds shall be done in the now pathless wilderness, and poets yet unborn shall sanctify the land.

And a frequent collaborator with the Hudson River School, landscape designer Frederick Law Olmstead (of Central Park and Olana fame) wrote directly about the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir debate in 1913:

“The monetary value attached to any object of beauty, whether natural or artificial, by public opinion… is a strangely fluctuating thing. For how many centuries were the most beautiful buildings of classic civilization regarded by the best minds of Europe as having no value higher than as stone quarries. What ruinously wasteful destruction was committed with entire self-approbation in the name of “improvement” during the period of the Renaissance upon the wonderful artistic inheritance from the Gothic period. What splendid gardens of the Renaissance were exultingly swept out of existence in the first flush of the fashion for informal landscape that came with the growing appreciation of the beauty of nature in the eighteenth century.

The lesson of history in this respect is unmistakable; a thing which many people have held to be of great and peculiar beauty and which cannot be replaced, even if the predominant men of the day fail to appreciate its beauty or are inclined to think its beauty would be increased by “improvements,” ought not to be destroyed or radically altered except under pressure of unavoidable necessity or after the most deliberate searched and humble inquiry as to whether the predominate opinion of the day is really right or is perhaps a passing phase colored by unconscious prejudice.

The United States deliberately undertook to preserve the scenery of the Yosemite National Park intact for the enjoyment of all future generations. The people of the United States are not yet so poor that they cannot afford to persevere in this purpose. To use the Hetch Hetchy as a San Francisco reservoir site would be to abandon that purpose by indirection, and would establish a precedent for abandoning the purpose of any and every park in case it conflicts with any considerable utilitarian interests.”

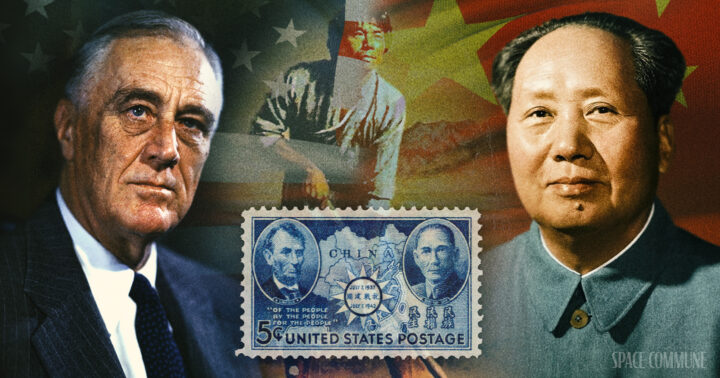

Examples of the projects that are a way out from the conservation/preservation debate include Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Hoover Dam, which was constructed with design elements to make it look more like the “inside of an Art Deco hotel lobby than a utilitarian power plant,” or “Disneyland in concrete” flanked with Winged Figures of the Republic that represent man’s victory over the elements.

And in China, the term “ecological civilization” has come to mean that giant infrastructure projects make the area more beautiful, not less, while increasing the living standards and flourishing of everyone around it:

If Americans can rekindle the spirit of the Hudson River School—infusing development with beauty and purpose, fostering coexistence between humanity and nature, and embracing the complexity of the sublime—we can move beyond the false binaries that have strangled our moral, creative, and political decisions. We simply do not have to choose between utilitarian pragmatism and romantic regression. We must instead create a future where infrastructure serves both function and beauty, and where progress is measured not just in terms of utility, but in its capacity to elevate the human spirit.