One of the greatest what-ifs in history happened in early 1945. After 14 years of bitter resistance against Japanese invaders, Mao Tse-Tung and Chou En-Lai wanted to meet face to face with American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The meeting was not so much about obtaining support against Japan; one way or another, Japan was doomed in the war. It was about what was to happen after the war. FDR had just convened the Bretton Woods Conference, where the United States sketched the economic architecture for a postwar order, which was meant to bind nations into peaceful cooperation through shared development, stable currencies, and access to credit.

In a conversation with American Foreign Service diplomat John Service, Mao made the Communists’ agenda clear. Their victory was assured, but they wanted to make sure China could quickly industrialize in a post-war world. Mao told Service:

China must industrialize. This can be done—in China— only by free enterprise and with the aid of foreign capital. Chinese and American interests are correlated and similar. They fit together, economically and politically. We can and must work together. The United States would find us more cooperative than the Kuomintang. We will not be afraid of democratic American influence—we will welcome it. We have no silly ideas of taking only Western mechanical techniques. Also we will not be interested in monopolistic, bureaucratic capitalism that stifles the economic development of the country and only enriches the officials. We will be interested in the most rapid possible development of the country on constructive and productive lines. First will be the raising of the living standard of the people… we will be interested in the welfare of the Chinese people.

This wasn’t just misdirection or posturing for a diplomat; even in internal CCP memos, China’s policy was clear:

Under conditions of observance of the principle of mutual advantage, we welcome international capital investments and technical cooperation.

However, the request for a Washington D.C. meeting was squashed by Roosevelt’s man in China, Ambassador Patrick J. Hurley. A few months later, FDR was dead, replaced by Harry Truman, a vice president who had only spoken privately with Roosevelt twice. To Britain’s delight, China remained divided, and Japan’s troops surrendered Hong Kong back to the Empire in August of 1945.

The dream of a U.S.–China partnership grounded in Bretton Woods died with FDR, giving way to decades of mistrust, isolation, multiple hot wars and one Cold War. Mao’s missed meeting of the minds with Roosevelt remains one of the great what-ifs of history.

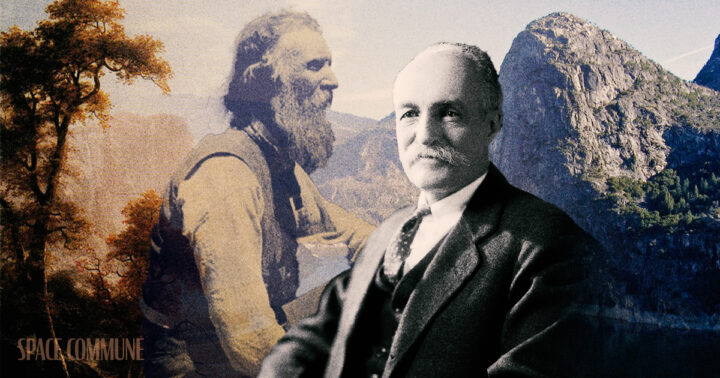

Mao, Sun Yat-Sen and the American System

Mao’s outlook didn’t emerge in a vacuum. He was a student of Sun Yat-sen, the father of modern China, whose 1919 plan The International Development of China read like a rough draft for Bretton Woods: railroads, canals, hydroelectric projects, and foreign credit to build industries. The plan was a response to the horrors of China’s century of humiliation, as well as World War I, charting a path forward away from colonialism and war, and towards the creation of higher living standards through internal improvements.

Sun openly embraced the Hamilton–Lincoln tradition of using state credit, infrastructure, and protective measures to create national prosperity. In his 1924 Three Principles of the People lectures, he declared:

The people’s livelihood requires that we regulate capital, develop state enterprises, and construct railways, canals, and industries, so that China may become strong and the people rich.

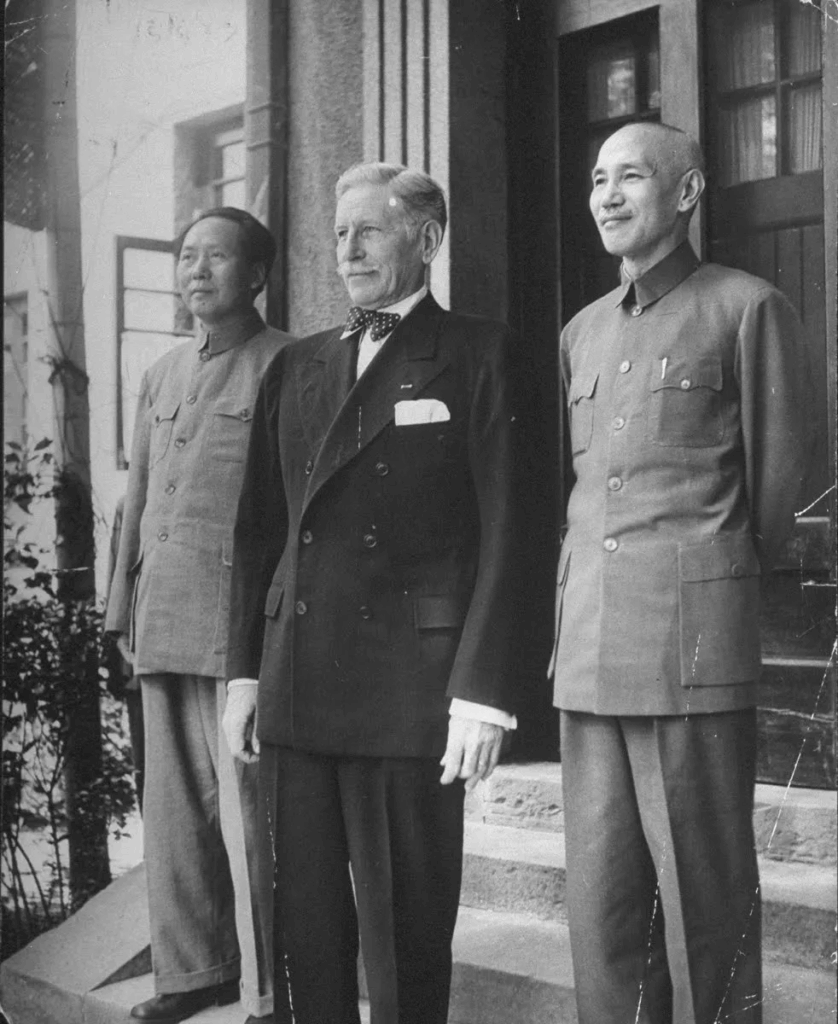

After Sun’s death in 1925, Mao and Chiang Kai-Shek battled over the future of China, with Mao coming to lead the Communist party in exile while Chiang Kai-Shek maneuvered his way to the head of Sun’s existing Kuomintang party.

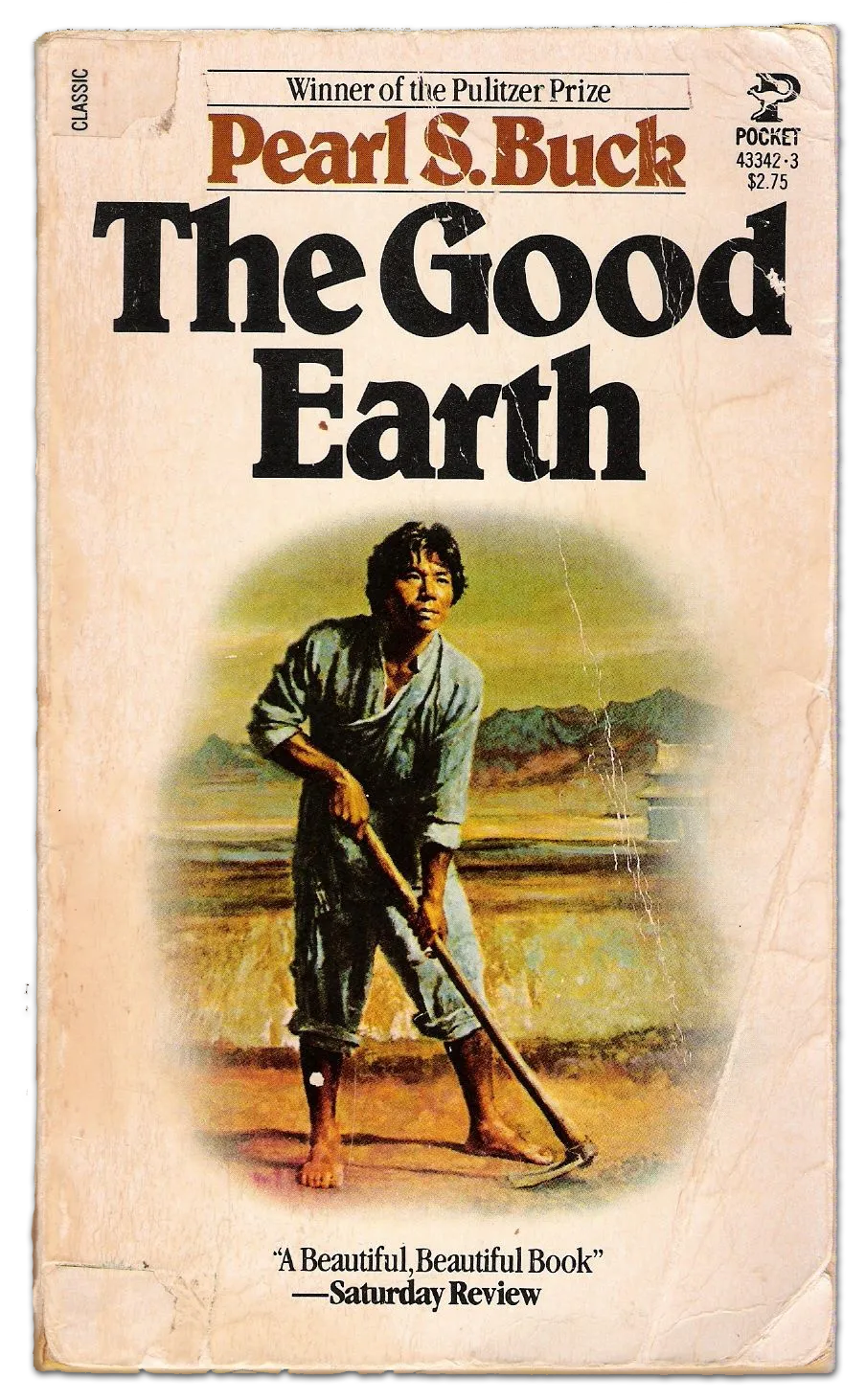

The China Mirage

By the 1930s, Chiang’s Kuomintang had abandoned Sun’s developmentalism in favor of bureaucratic graft and foreign dependency. His regime was propped up by what was termed by James Bradley as the “China Mirage.”

The mirage was built on the legacy and fortunes of the 19th century opium trade, where American missionaries, traders, and bankers crafted a vision of China as a vast, spiritually receptive, and economically ripe nation waiting for Western guidance. China could be an American-guided bulwark against Bolshevism in the East.

Did you know Space Commune is on Telegram? Join our channel and never miss an update!

The fantasy was epitomized by the copasetic relationship between the Western-educated Chiang Kai-Shek, his wife Soong Mei-ling, and the Time and Life publisher Henry Luce. The hellspawned Luce, born to missionary parents in China and an open admirer of Churchill and Mussolini, saw China as central to his vision of an American Century, a new world order where spiritually malleable countries could be economically guided by the United States.

After the xenophobic 19th century American campaign of “The Chinese Must Go,” perhaps the China Mirage could’ve been seen as a positive thing. But it was all to prop up a failing regime, which became more and more brutal as it lost power to the Communists. John Service wrote:

The Nationalist Government of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang grew weaker with every passing month… This made it impossible for the KMT to generate popular support from the impoverished peasantry and caused a growing disillusionment of the small but influential educated groups… The Communists, on the other hand, steadily expanded their base of support… and had become, by the war’s end, the certain inheritors of China’s future.

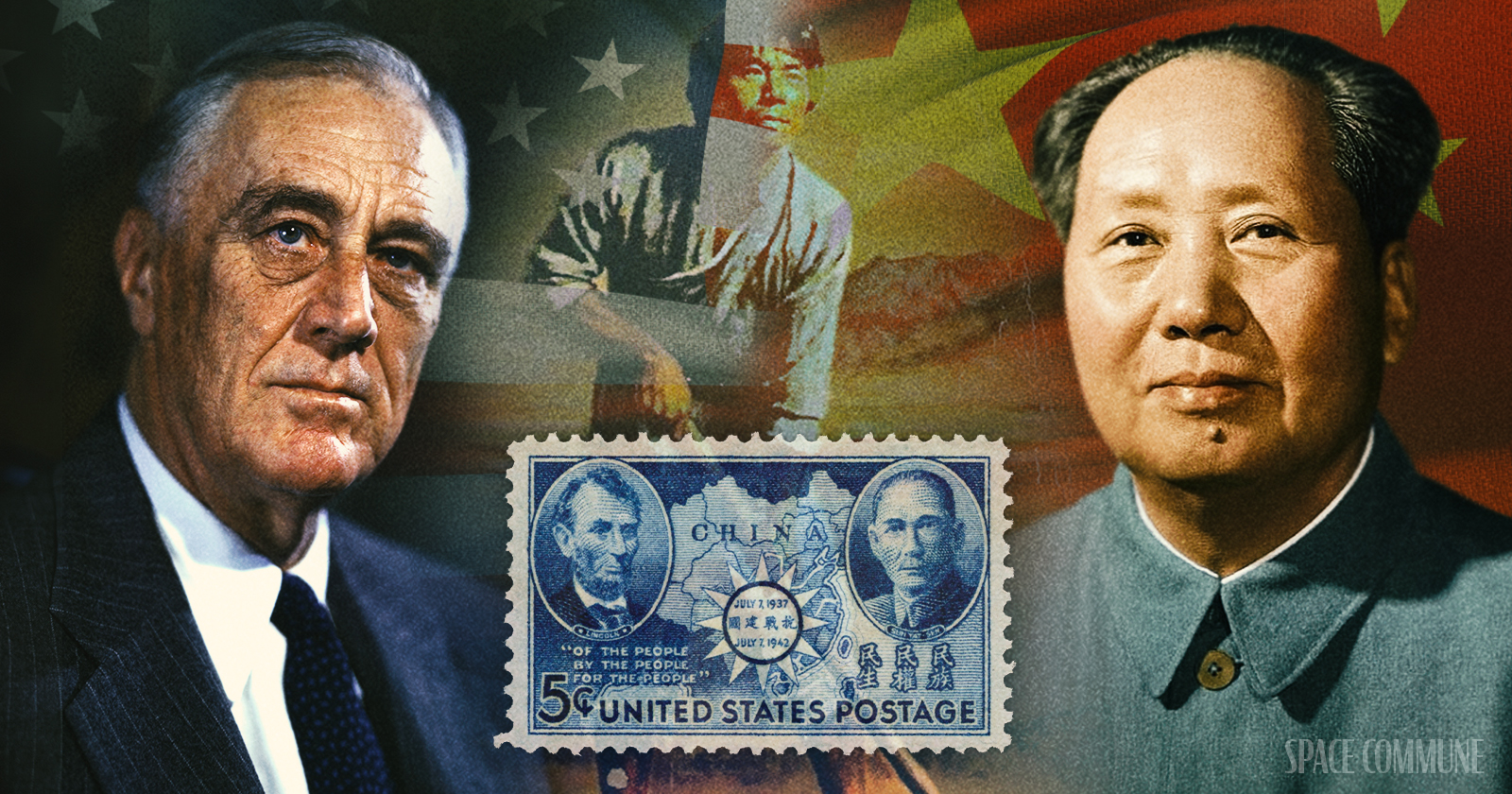

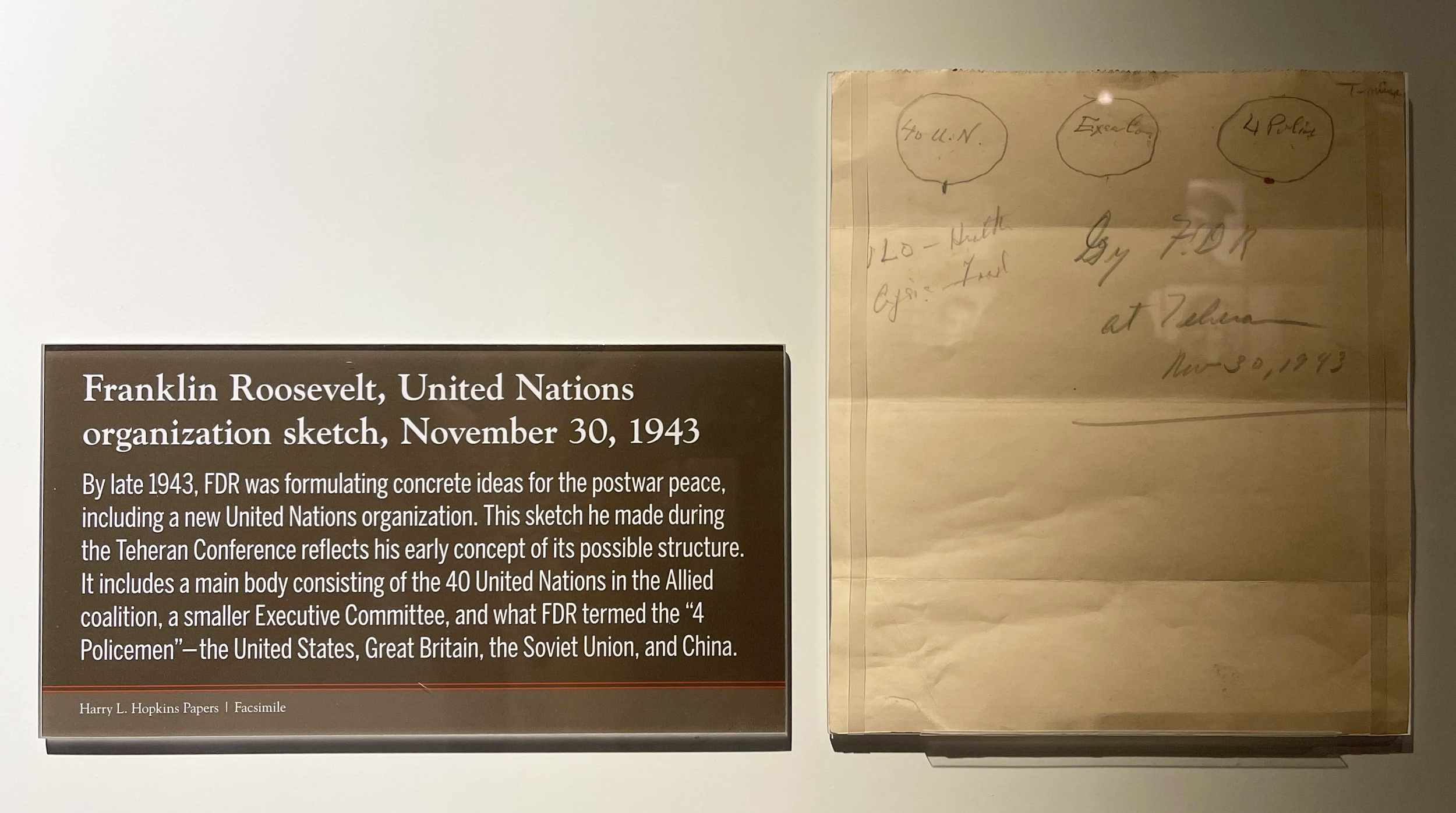

FDR’s Vision for a “Strong China” and Bretton Woods

FDR’s Delano family fortune came largely from the opium trade, although it’s not clear that he fully understood that. His vision for a post-war economic and diplomatic architecture at Bretton Woods, was a sharp turn from British-led opium slavery. Credit would be used for infrastructure and industry that could peacefully liberate the world from the legacy of imperialism.

To accomplish this, he envisioned “four policemen” of the world that would oversee the process: the US, Britain, Russia and China. During World War Two, three of those four nations demonstrated they had the industrial and military capacity to play that role; China, as an occupied nation on the verge of a civil war, did not. However, if China could resolve its internal conflict, the most populous nation in the world would take its place as the fourth policeman.

The Mephistophelean Winston Churchill and the British, were viciously opposed to the idea of a strong China, owing to their interests in Hong Kong and Indochina at large. In a briefing sent back to Roosevelt, American ambassador to China John Hurley wrote about a discussion on the matter with Churchill:

Questions pertaining to the reconquest of colonial and imperial territory with American men and lend-lease supplies and the question pertaining to Hong Kong and other problems were interjected by the British… Churchill flatly stated that he would fight for Hong Kong to a finish. In fact he used the expression ‘Hong Kong will be eliminated from the British Empire only over my dead body!’

I then pointed out that if the British decline to observe the principles of the Atlantic Charter and continue to hold Hong Kong , then Russia would possibly make demands in regard to areas in North China. Churchill’s response was that Britain was not bound by the Atlantic Charter, and that the policy of a strong China was a “great American illusion.”

FDR’s Distrust for the State Department Led to Something Worse

As his son Elliott Roosevelt wrote in As He Saw It, FDR famously had a distrust for the State Department:

I was told six years ago to clean out that State Department. It’s like the British Foreign Office.

FDR knew that his State Department was severely compromised, and he needed men he could trust to handle foreign affairs. Although General Patrick J. Hurley was a Republican who chaired Herbert Hoover’s first presidential campaign, he shared a strong suspicion of the British and had fended them off in during diplomatic negotiations in Iran. Chiang Kai-Shek personally requested that Hurley be given the China ambassador assignment, saying “has my complete confidence” in dealing with the Communists.

Roosevelt told his son, “I wish I had more men like Pat… if anybody can straighten out the mess of internal Chinese politics, he’s the man.”

Hurley was correct in his opposition to British interests. But he didn’t understand that Mao and the Communists in the North were the only force capable of not only beating Japan, but developing a “strong China” that was capable of throwing off the shackles of British imperialism.

The buffoonish Hurley was rendered incapable of understanding this after decades of China Mirage propaganda, and also after USSR officials assured him they wouldn’t support Mao over Chiang Kai-Shek. He assumed that without support from Moscow, the Communists would have no choice but to come into the fold with the KMT and form a unified China. Therefore, Hurley pursued a policy of exclusively supporting Chiang.

His lack of ability to see the truth in China, despite overwhelming reports to the contrary, was quickly exploited by the fiendish Chiang, as well as the British. Hurley came to perceive any questioning of the viability of the KMT regime as a personal attack on his ability to bring the country together. Foreign service officers referred to being fired by him as being “Hurleyed” out of China. The perfidious British Ambassador Lord Halifax noted:

The State Department has one bucking-bronco ambassador in its hands and it does not quite know what to do with him. He is [the] ebullient, energetic Patrick J. Hurley.

After FDR’s death in early 1945, the new team at the State Department contrasted Hurley’s reports with the situation on the ground. They wrote that he was refusing to allow any reporting on clashes between the KMT and communist troops:

We have definite reason to believe that General Hurley has ordered that only political reports favorable to the Chinese National Government may be made to the Department, and it is apparent that we can no longer count on receiving factual and objective reports in regard to all aspects of the situation.

Hurley had a child-like understanding of the differences between the KMT and the Communists. He wrote there was “very little difference” between their ideologies, as both were “striving for democratic principles.” Meanwhile, John Service, in a Foreign Service memo that must’ve rankled Hurley, wrote that Chiang Kai-Shek’s 1943 book, China’s Destiny, was so riddled with xenophobia and fascist rhetoric that it was China’s Mein Kampf.

The Chinese War Effort

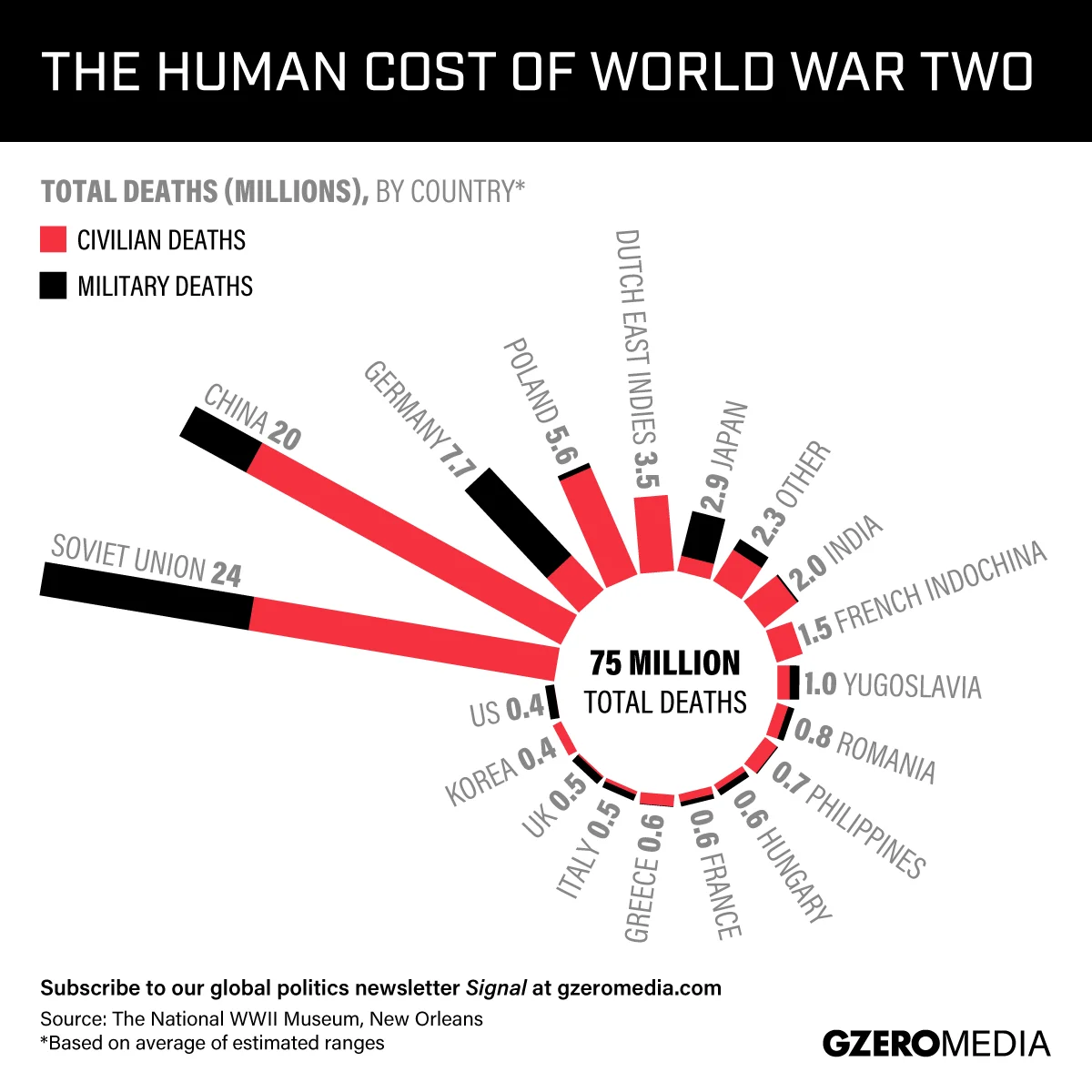

It’s well-known that 75 to 80% of the German fighting force was exhausted in Russia on the Eastern Front, at the cost of tens of millions of Russian lives. It’s less-known that to occupy Manchuria and Northern China, Japan committed roughly 70% of its fighting force, again with the macabre cost of tens of millions of lives. Without the resistance in China, Japan could have put up a much stiffer fight in the Pacific.

The nature of the fight in China was much different than in USSR. Rather than a united front against a foreign, fascistic invader, China’s war was three-sided; there were the Japanese, who lightly occupied a massive land area, the Communists, who engaged in guerrilla warfare and moved freely through the occupied north, and the KMT, whose troops were mostly positioned to maintain borders against the Communists and not the Japanese. The communist armies constantly harassed the Japanese occupiers.

When witnessed by unbiased observers like John Service, it was clear that the Mandate of Heaven was being passed to Mao and the Communists:

This total mobilization is based upon and has been made possible by what amounts to an economic, political, and social revolution. The Japanese are being fought now not merely because they are foreign invaders, but because they deny this revolution. Unless the Kuomintang goes as far as the Communists in political and economic reform, the Communists will be the dominant force in China within a comparatively few years.

The United States intelligence and diplomatic communities began to debate whether or not the nation should remain loyal to its outdated China Mirage. If they supported the winning side in China, they could beat Japan faster, help resolve the brewing civil war, and set the country up for Bretton Woods-style post-war development. Again, it was John Service making an astute calculation in real time:

The Kuomintang cannot unify the country because it derives its support from the economically most conservative groups, who wish the retention of China’s economically and socially backward agrarian society. These groups are incapable of bringing about China’s industrialization, although they pay this objective elaborate lip service. They are also committed to the maintenance of an order which by its very nature fosters particularism and resists modern centralization… If the Kuomintang is actually what it claims to be—democratic and sincerely anxious to defeat the Japanese as quickly as possible—it should not oppose our insistence on giving at least proportional aid to the Communists.

But to the delight of Chiang Kai-Shek, Ambassador Hurley blustered that cooperation with Mao’s forces “would constitute recognition of the Communist Party as an armed belligerent,” and lead to “destruction of the National Government… chaos and civil war, and a defeat of America’s policy in China.”

American diplomat John Davies observed that the Chinese Communists felt that the British were more than happy to see China being divided into spheres of influence:

They fear a marriage of convenience between Chiang and the British whereby the Generalissimo would get British support in return for special concessions in South China… so the Chinese Communists watch us with mixed feelings. If we continue to reject them and support an unreconstructed Chiang, they see us becoming their enemy. But they would prefer to be friends.”

Mao pleaded that “to give arms only to the [KMT Nationalists] will in its effect be interference… there will have to be American cooperation with both Chinese forces. The U.S. Army can see… that we have popular support and can fight.”

Mao Wanted to Meet with Roosevelt in Washington

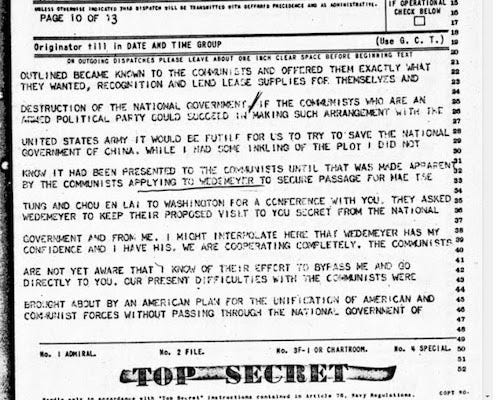

Mao Tse-tung and Chou En-lai were correct in assuming that Roosevelt had a lot on his plate in early 1945, and that his trust of Ambassador Hurley was blinding him to the truth on the ground in China. They sent a request that was transcribed by American military officials:

[They] want [to] dispatch to America an unofficial group to interpret and explain to American civilians and officials interested the present situation and problems of China. Next is strictly off record suggestion by same: Mao and Chou will be immediately available either singly or together for exploratory conference at Washington, should President Roosevelt express desire to receive them at White House as leaders of a primary Chinese party.

However, Ambassador Hurley interpreted the request as yet another slight against his ability to unify China. He mentioned it in a much larger memo to Roosevelt, but framed it as the Communists trying to undermine his authority, not as a legitimate request.

It is believed that Hurley convinced Roosevelt that the recent Yalta agreement would weaken the Chinese Communists to the point that they’d have to submit to collaboration with the KMT by the spring. Therefore, Roosevelt’s stance remained that the Communists and the KMT would have to find a way to work together. Roosevelt died shortly afterward.

What if Mao and Roosevelt Met?

If Roosevelt and Mao had met in early 1945, the postwar world might have taken an entirely different shape.

As we previously wrote, the conditions of China’s 1970s rapprochement with Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger and the United States were almost too much to bear: in exchange for opening back up to Western capital, Mao had to admit that China had a “population problem.” The resulting One Child Policy was the toast of Western Malthusian freaks, the real-life realization of Kissinger’s loathsome NSSM-200 report.

Nonetheless, until the day he died, Henry Kissinger remained welcomed and respected in China. That is owed to the fact that he acknowledged China’s rich history and culture, as evidenced by his 2011 book On China. Even though he’s remembered internationally as a butcher, Chinese diplomats knew that he was smart enough to make a deal with the winning side, unlike Ambassador Hurley.

If Mao had met with Roosevelt directly, and been able to appeal to him on a shared vision of the post-war world, perhaps several great crises could have been averted or lessened. Perhaps the Chinese Civil War could’ve been shortened or avoided. Perhaps the United States could have accelerated China’s industrialization process and made the Great Leap Forward less painful. Without the festering resentments of the civil war and Washington’s support of Chiang, the Korean and Vietnam wars might not have happened.

Barbara Tuchman, reflecting on this in 1973 for Foreign Affairs, put it bluntly:

Three years of civil war in a country desperately weary of war and misgovernment might have been curtailed… The United States, guiltless of prolonging the civil war by consistently aiding the certain loser, would not have aroused the profound antagonism of the ultimate winner… We might not have come to Korea. We might not have come to Vietnam.

Instead, Roosevelt died, Truman inherited a China policy shaped by Henry Luce and Hurley’s illusions, and Mao never set foot in Washington. The British held onto Hong Kong until 1997, which remains as a breeding ground for color revolution and foreign manipulation to this day. Henry Kissinger got to be the representative of America to China, not Roosevelt. The FDR vision of Bretton Woods, a global architecture built not on spheres of influence, but on peaceful development and cooperation, was buried in the ruins of the missed meeting.