As the bumper sticker says, “Water is Life.” Some have taken that to mean that wherever water is, it should stay there. Others believe that water is a finite, utilitarian resource that should be sold to the highest bidder, regulated by market discipline. But in debates and proposals that stretch back to our nation’s founding, there’s a higher use for water. The answers lie in Hamiltonian economics, the grand canal plans of Alexander von Humboldt, and in the bold vision of John F. Kennedy’s water and power proposals.

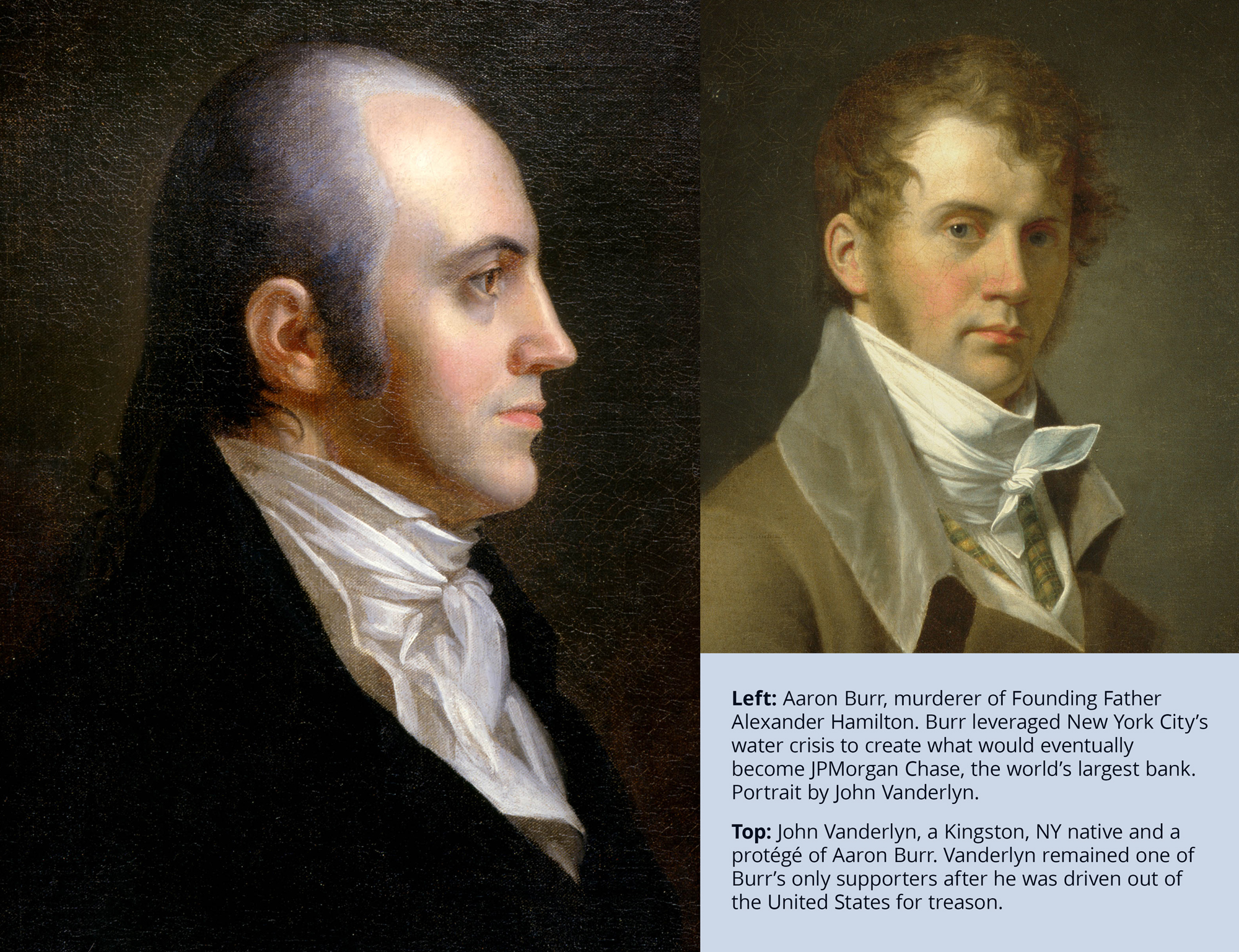

Hamilton vs. Burr: Creating a Reservoir of Cash

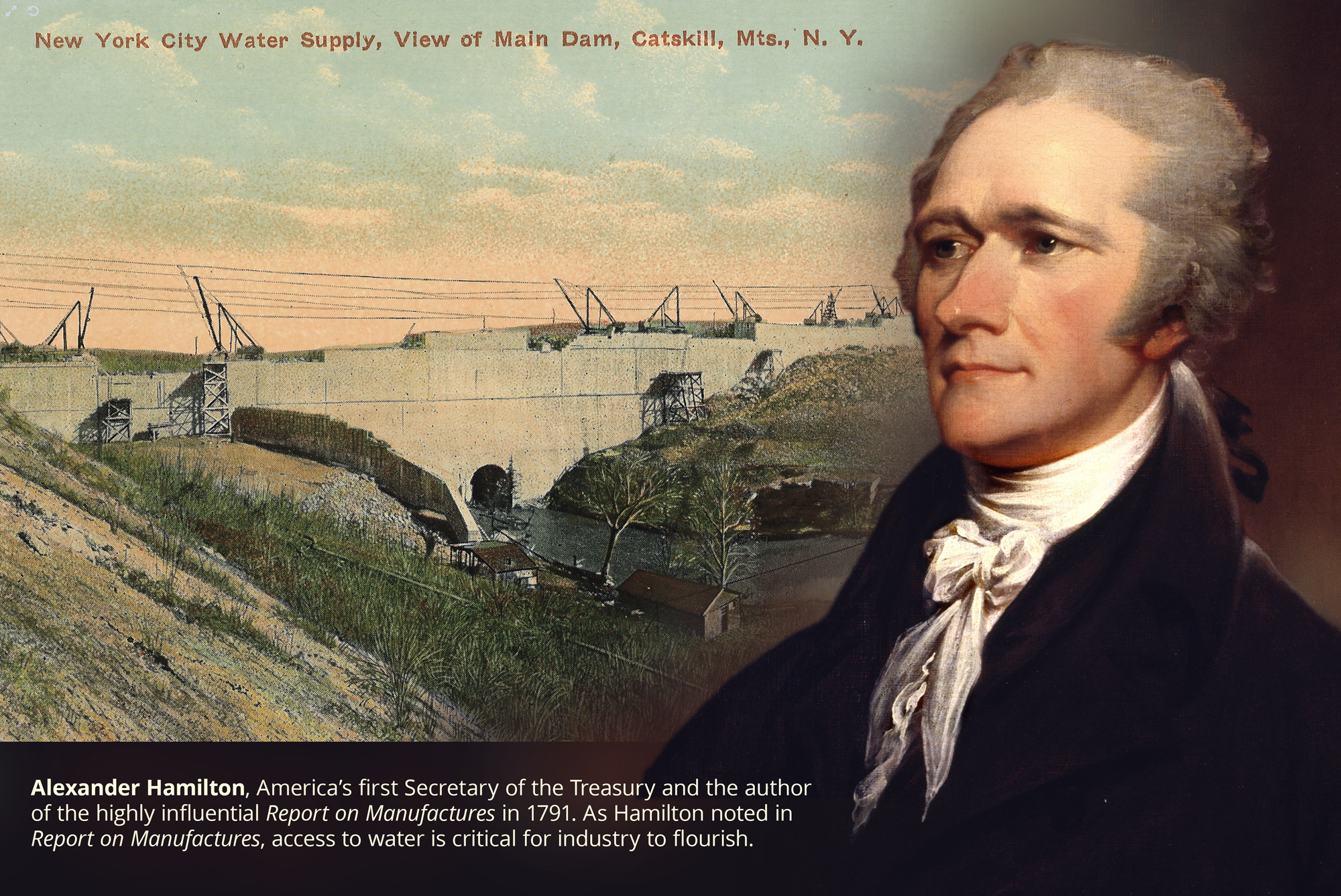

In the 1790s, New York City’s population was significantly smaller than it is today, with only 33,000 residents compared to the current 8.2 million. Despite its relatively small size, it was the nation’s largest city and was experiencing rapid growth, largely due to the economic policies of Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, who helped found the Bank of New York in 1784, and whose 1791 Report on Manufactures had a profound impact.

Hamilton’s policies centered on establishing a national bank to foster a stable economic environment. This stability would facilitate long-term infrastructure investments, such as roads, canals, and ports, which in turn would promote industrial development and increase productivity across various sectors, including agriculture, mining, and manufacturing. To protect this burgeoning production, Hamilton advocated for tariffs that would encourage the export of valuable goods over raw materials, further contributing to the expansion of port cities like New York.

Hamilton recognized that access to water was essential for industry to thrive. By 1798, New York City faced a severe water crisis that threatened not only its industrial growth but also the health and safety of its residents, through outbreaks of yellow fever. In the same year, the loathsome Thomas Malthus published his Essay on the Principle of Population. In a direct divergence from Malthus, New York City was actively pursuing infrastructure projects that could burst through supposed Malthusian limits to growth by securing a clean water supply for an expanding population.

Watch my Rising Tide Foundation presentation on the topic of Burr, Hamilton, and Mega-Infrastructure projects here:

It was in this context that Aaron Burr, a political adversary of Hamilton, saw an opportunity. He proposed the creation of The Manhattan Company, ostensibly to provide clean water from the Bronx River to the city, and conditionally gained Hamilton’s support for the plan. However, the company’s charter contained a hidden clause that allowed Burr to use surplus capital for “monied transactions,” which was in reality a scheme to establish a private bank.

Did you know Space Commune is on Telegram? Join our channel and never miss an update!

Burr’s true intention was to use the city’s water crisis to create a rival bank to Hamilton’s Bank of New York and the networks of the Society of Cincinnati, aiming to offer favorable terms to himself and his political allies at the massively corrupt Tammany Hall.

Alexander Hamilton later wrote that Burr, “by a trick established a Bank, a perfect monster in its principles; but a very convenient instrument of profit & influence.”

The bank is widely credited as financing the election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800 with a “reservoir” of cash.

Instead of supporting potentiality and industry as Hamilton would have hoped, the Manhattan Company invested minimally in water infrastructure, ultimately hindering the city’s development. The water supply remained inadequate and polluted, contributing to yellow fever outbreaks and uncontrolled fires. Thus, it was not the limitations of natural resources, as Malthus might suggest, that constrained the city’s growth, but rather exploitative financial practices.

Despite losing its monopoly, the Manhattan Company maintained a token presence as a water provider, ceremonially pumping water from a well every day until 1923. The company eventually merged with Chase to form Chase Manhattan Bank in 1955, which then merged with J.P. Morgan & Co. in 2000 to become J.P. Morgan Chase. The pistols used in the Burr-Hamilton duel are still kept at J.P. Morgan Chase headquarters in New York City as a macabre reminder of the affair.

Upon fleeing the United States after becoming known as a murderer, Burr ended up staying with Jeremy Bentham, the British philosopher who both wrote the book Defence of Usury, and pioneered the concept of utilitarianism; i.e., that any action is right insofar as it increases happiness, and wrong insofar as it increases pain.

The Environmentalist Trend to Benthamite Utilitarianism

Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism laid the groundwork for the false environmentalist paradigm that persists to this day in the West.

For utilitarians, there is the concept of Conservation: a technocratic, entropic view of natural resource management where experts and monopolists manage an ever-shrinking pie. For transcendentalists, there’s Preservation, as some oligarchic elements prefer that we regress to a natural, primitive state where Darwinian survival of the fittest can take its course unfettered, a la the writings of figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson or John Ruskin.

Second only to Burr, perhaps the most influential American proponent of Bentham’s philosophies was the tree-hugging pioneer, Gifford Pinchot, who was Theodore Roosevelt’s forestry czar. Pinchot is seen as the grandaddy of conservation, epitomized with his public feud with Transcendental Preservationist John Muir over the Hetch Hetchy Dam outside of San Francisco.

50 years before the Club of Rome’s loathsome Limits to Growth report, Pinchot even proposed a sort of global system of entropic control that would prevent sovereign nation-states to develop as they see fit:

“The conservation of natural resources is the key to the future. It is the key to the safety and prosperity of the American people, and all the people of the world, for all time to come. The very existence of our Nation, and of all the rest, depends on conserving the resources which are the foundation of its life. That is why Conservation is the greatest material question of all. … Moreover, Conservation is a foundation of permanent peace among the nations.”

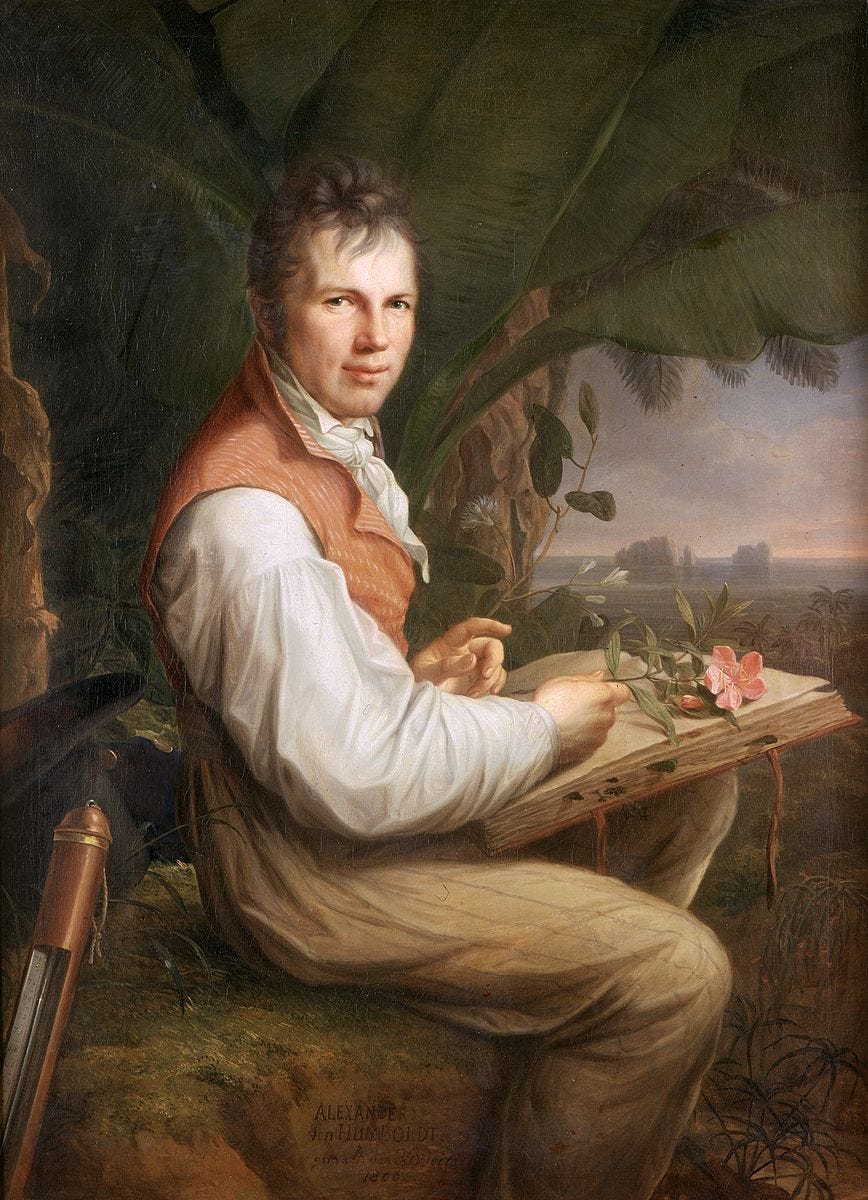

Enter Alexander von Humboldt

After Hamilton’s death, the next figure to continue Hamilton’s legacy with infrastructure proposals on the American continent was the German polymath and explorer Alexander von Humboldt. Humboldt toured South America from 1799 to 1804 to find out how “all of the forces of nature are interlaced and interwoven.”

Instead of coming away with a Gaia-worshipping perspective on how to stop human development, Humboldt was convinced that massive infrastructure projects to move water from where it was, to where it wasn’t, were needed for the American continent to thrive. This was consistent with his belief in an inherent right to individual freedom for all humankind.

This view was best shown in his timeless 1848 masterpiece, Cosmos: Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe. Two centuries after Thomas Hobbes’ nihilistic declaration of war of “all against all,” decades after Bentham’s reduction of man to simply pursuing pleasure and pain, and a decade before Charles Darwin wrote his loathsome On the Origin of Species, Humboldt wrote of a harmony of species that could be mastered by human beings:

Nature considered rationally, that is to say, submitted to the process of thought, is a unity in diversity of phenomena; a harmony, blending together all created things, however dissimilar in form and attributes; one great whole animated by the breath of life. The most important result of a rational inquiry into nature is, therefore, to establish the unity and harmony of this stupendous mass of force and matter.”

This harmony was predicated on “the suppression of all unnecessary detail,” where reason could then “grasp all that might otherwise escape the limited range of the senses.” Man’s “creative intellectual power” could then be harnessed to allow for “unrestrained development of the physical powers.” Harmony was something that could be created through international cooperation and development of mega-infrastructure projects, and not, as Gifford Pinchot advocated in the previous section, through simply hunkering down and conserving existing resources.

Writing in his Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain in 1811, some of Humboldt’s infrastructure ideas included a South American inland transportation network, which was a 4,000 mile plan to link the Orinoco, Amazon and Rio de la Plata basins, nine unique interoceanic canal routes (including mapping out the Panama Canal), and an integrated hydraulic system for irrigation in Mexico City.

The Rise of NYC’s Mega-Infrastructure Projects

While figures like Bentham, Humboldt and Darwin duked out Western philosophies toward development, New York City still needed water.

The miserable failure of Aaron Burr’s Manhattan Company led to the city’s aggressive search for water in upstate New York, starting with the Croton Aqueduct in Westchester, which was already insufficient by the 1850s. A second Croton Aqueduct, and a new Croton dam, the largest in the world at the time, were completed by 1906. But it still wasn’t enough, and the surrounding Catskills region, once the bosom of the Hudson River School and patriotic writers like Washington Irving and James Fennimore Cooper, was targeted.

Johannes Hardenbergh acquired what is known as the “Hardenbergh Patent” of two million acres in the Hudson Valley and Catskills from the British Crown in 1708. Despite its publicity from the Hudson River School, Rip Van Winkle and the Leatherstocking Tales’ Natty Bumpo, the region did not develop at the pace of the other colonies. A one year boom from the city of Kingston being named New York’s first capital ended quickly with the British burning it down in 1777, as part of their failed attempt to split the colonies in two by controlling the Hudson River.

The burning of Kingston seemingly doomed the region to be underdeveloped, as boom and bust cycles of tanning, bluestone and lumber extraction, and coal shipping, and small-scale farming operations all lent to an unreliable physical economy. Governments had to lean heavily on speculation-driven property taxes in lieu of a physical economy, which frequently led to defaults, resulting in Kingston’s county being the only tax delinquent one in New York in 1884.

The crisis forced an ignominious precedent; instead of developing infrastructure that could increase the productive capacity of labor, they sold off 32,731 acres of land to New York State to settle its tax debts, under the guide of creating a “forever wild” Forest Preserve called Catskill Park. Today, we can see echoes of this exact practice through various “sustainable development” schemes calling for “30×30”, or preserving 30% of all land from development by 2030.

While preservation often includes maintaining property tax payments, it is in exchange for keeping communities in a state of arrested development. In the Catskill Park region, preservation remains at tension with the region’s ongoing housing, affordability and economic crises.

A stipulation in the Catskill Park “forever wild” bill stated that watershed protection was a principal reason for its establishment. In no coincidence the following year, Scientific American published an article describing the framework that New York City would eventually adopt in constructing its Catskill waterworks. The high peaks of the Catskills Mountains created catchment basins for water, while the elevation of the region compared to New York City meant that water could be propelled by the effects of gravity.

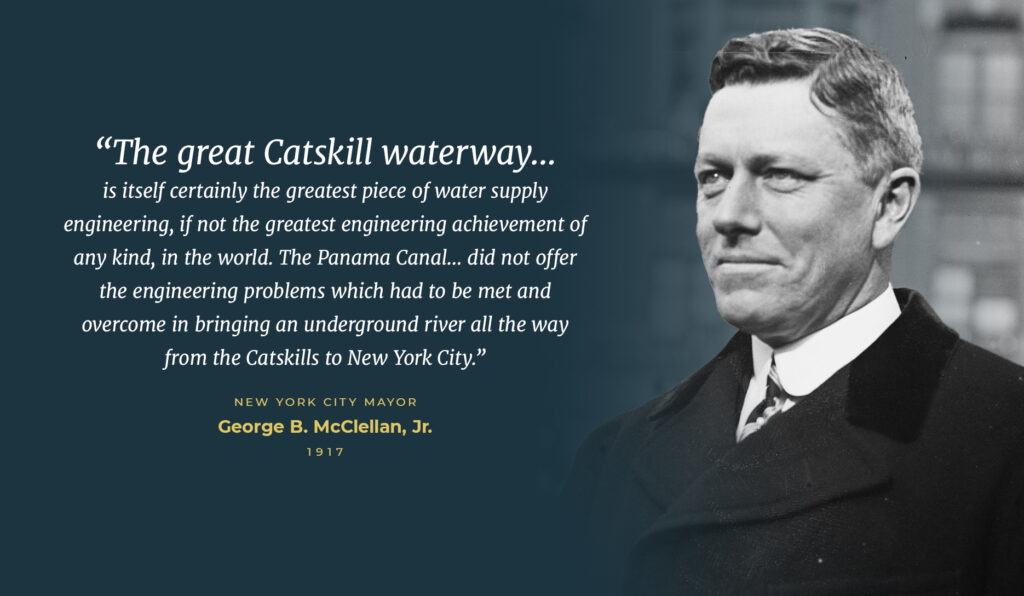

The watershed was being protected in advance of the world’s next great mega-engineering project: the Ashokan Reservoir, which by its completion in 1917, was considered a more impressive engineering feat than even Humboldt’s Panama Canal.

Upstate New York’s Economic Handcuffs

The Ashokan Reservoir’s aqueduct stretches 120 miles to its end on Staten Island. It was built through pressure tunnels carved deep into solid rock, which transported water beneath the Hudson River near Storm King Mountain via the Rondout Siphon, which descends 1,114 feet below sea level.

The waterway was initially a triumph of Hamilton’s American System over Burr. Government-backed mega-infrastructure was going to enable New York City to get some of the most abundant and high-quality water it ever had access to. New York City’s population doubled from the time construction began on the reservoir to when it was finished. By the time the city finished most of its Catskills water infrastructure projects in the 1960s, its population had grown from 3.4M in 1900 to 7.9M in 1970.

The best mega-engineering projects are known for their halo effects; not just conveying resources, but transforming the earth for the benefit of all around them. But unfortunately for the neighbors of the Ashokan Reservoir, the Benthamite view of human development eventually won out, prioritizing New York, the financial capital of the world, over regional prosperity and development.

The Filtration Plant That Was Was Promised

“The question that would come to dominate New York City’s relationship with Catskill residents in the 1990s—should it build a costly filtration plant to improve water quality or instead enact strict regulations to reduce pollution on the watershed—first reared its head, albeit less starkly, seventy-five years earlier.”

David Soll, Empire of Water: An Environmental and Political History of the New York City Water Supply (2013)

The original plans for the reservoir included building a $17.5 million filtration plant in Westchester. But in 1915, Ashokan Reservoir engineer John Freeman backtracked, saying he “could see no reason why this water cannot be prudently delivered for some years without filtration, if the present financial needs of the City require deferring such expenditures.”

This deferral ended up killing the possibility of building a water filtration plant. Instead, New York City decided that “natural filtration,” i.e. preventing industrial and agricultural development for hundreds of square miles around the reservoir, was more cost-effective.

The Filtration Avoidance Determination (FAD): Keeping the Catskills Poor for NYC’s Water?

This decision to avoid a water filtration plant, which would have cost over $5B in 1915 when adjusted for inflation, meant that the usual benefits of hosting mega-infrastructure projects never got passed on to the host communities.

The construction of reservoirs always meant that there would be a decade of work for local job-seekers. But the long-term negative effects have far outweighed that: in Ulster County alone, 32% of the total land mass is protected from development.

Considering the rates of poverty, opioid addiction and other forms of misery in the host communities, it’s clear that the decision to not build a filtration plant has had a devastating cost while saving New Yorkers a relatively small amount of money, which could have been raised through bonding and paid off over time.

A Watershed Moment for the Catskills

In the 1990s, New York City and their water system host communities reached a breaking point. A new law required that any US municipality with a population over 10,000 had to filter its water or acquire a Filtration Avoidance Determination (FAD), by proving that there are enough “natural” barriers and preserved lands around the municipality’s water source.

“It should be that our best management practices are enough… now they want to control life on the hills. Well, they moved us out of the hills. They put us on the hills in the first place.”

Assemblyman Dick Coombe, R-Grahamsville, 1990

Watershed communities mounted a counterforce to New York City’s plans to use more preserved land around the reservoirs. They were suffering from a lost century of economic underdevelopment, leading to spiraling inequality and gentrification: real estate prices were driven up without increasing the productive power of labor. The only purchasers of land were either New York City or wealthy second homeowners.

“While these land acquisitions may be protecting the city’s water, they also may be causing a new wave of indirect damages to watershed communities—a slow-moving expulsion. (Hoffman 2005, 2008, 2010).

Poverty rates increased throughout the 1990s, and approximately 40 percent of renters cannot afford fair market rents in these communities. This has affected the children of current residents who cannot find housing of their own. Enforcement of water regulations is also keeping business out, which negatively impacts their ability to find work.

More than 60 percent of Olive’s land is already owned by the state or the city. There is precious little space for people to live, and the tax burden has shifted to fewer and fewer residents. Taxes are based on assessed property values, and because city-owned land is without structures, the city pays little in taxes.”

– Taking Our Water for the City, April Beisaw, 2022

A third party emerged in the negotiations: New York City’s powerful and well-funded environmentalists, including Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the lead attorney of both Riverkeeper and the National Resources Defense Council. He earned the derisive moniker “Fifth-Avenue Environmentalist” from former Town of Hunter supervisor Anthony Bucca. RFK Jr. and his cronies argued strongly against allowing the rural towns to develop as they saw fit, arguing that “natural” filtration was the only solution.

“Spending so much on filtration at a time when every level of government is crying poverty would no doubt undermine watershed protection. There would be little, if any, money left over for buying buffer lands, regulating development, beefing up enforcement and otherwise protecting the supply. In fact DEP officials have said that the high cost of filtration would probably spur calls for the city to sell some of the buffer lands it now owns. Filtration would also foster a sense that watershed protection was unnecessary.”

Riverkeeper, The Legend of City Water, 1991

RFK Jr. and New York City won, and in 1997, a New York City Watershed Memorandum of Agreement pledged over a billion dollars to a formal Land Acquisition Program, which continued unaltered until 2024, when the many acquisitions were stopped.

Is natural filtration better than a manmade facility? The answer might be in a 2005 essay by environmental philosophy Mark Sagoff, who dubbed the concept of natural filtration The Catskills Parable.

He wrote that impurities and pathogenic microorganisms are more likely to be introduced into the water by the surrounding natural landscape (such as from animal scat) than removed by it; and that the determination of the amount of land that needed to be acquired was arrived at through political and not as a means of environmental necessity:

“Few of us wish to admit that we benefit from nature not by preserving but by “improving” it—for example, by plowing a field, building a road, constructing a house, drilling a well, damming a river, farming a salmon or oyster, or altering a genome. Most of us would rather believe that Nature knows best. We will therefore repeat… the Catskills parable even though it is factually false.”

– Mark Sagoff

Bold Plans or Sparse Utilitarianism?

The New York City water system represents the Benthamite utilitarian thinking that has crowded out the American System vision of Hamilton. The benefit to the infrastructure host communities was an afterthought; the focus was always on how to bring as much water to New York City for the least amount of money.

An alternative to this paradigm was proposed by none other than RFK Jr.’s uncle, President John F. Kennedy. In 1962, he toured the United States to tout a national water infrastructure project that built on the visions of Hamilton, Humboldt and other visionaries. In this video, he celebrates the opening the Flaming Gorge Dam in Salt Lake City, Utah, just two months before his assassination:

After his death, JFK’s vision lived on. The man standing his left in the video, Utah Senator Frank Moss, wrote a book in 1967 called The Water Crisis, where he lauded the North American Water and Power Alliance proposal as an effective way of solving America’s supply and pollution problems.

Moss wrote:

We are now gathering data on a bold new plan that could solve the continent’s water problems for the next 100 years. The idea is to collect surplus water from the rivers of Alaska, the Yukon Territory, and British Columbia, and draw it southward through a gigantic system of canals, reservoirs, tunnels, and rivers.

The heart of the system would be a vast reservoir-lake, 500 miles long. This would fill to overflowing a gorge known as the Rocky Mountain Trench, high in the upper reaches of the Columbia, Fraser, and Kootenay Rivers. Situated near Banff and Jasper National Parks, this great man-made lake would open up a vast new recreational area, in addition to watering the West from central Canada deep into Mexico. Of course, this plan would require the endorsement and cooperation of the Canadian and Mexican governments, and they have already indicated their interest.

Here’s what the system would do:

Bring to the West its own man-made Mississippi River. The other ingredients for development are already there, but advancement will be limited until the water arrives.

Provide a navigable waterway from Vancouver on the Pacific to Duluth on Lake Superior.Raise the level of the Great Lakes enough to increase electric power production at Niagara by 50 percent and cleanse the lakes of pollution. Not only double the water supply for all our own arid states but also provide plentiful irrigation water for northern Mexico.

Finally, provide an adequate water supply for the United States for the next 100 years.

The water and power could give birth to new mining, manufacturing, commercial, and financial enterprises. Great modern cities could rise in Utah, Nevada, and Arizona.

The rich soil would literally spring to life and produce a vast new food supply for our growing population. Hunting, fishing, boating—indeed, all the fine recreational opportunities of the great West—would flourish. The mountains, deserts, and vast prairies would beckon other Americans, who could now have a choice of where to live their lives and how to live them.

Contrast these bold plans to the sparse utilitarianism of New York City’s water system.

Regaining the Political Will to Build Again

The story of the Catskills, like the duel between Hamilton and Burr, is more than a local tragedy. It is a lesson in the kind of nation we’ve chosen to be, and a warning about the consequences of choosing small, cynical thinking over grand designs for human development.

Where Hamilton saw water as the foundation for industry and growth, Burr saw it as a means for private gain. Where Humboldt envisioned rivers as the connective tissue of a continental civilization, today’s utilitarian planners reduce nature to a commodity to be preserved or extracted—never developed with purpose. And while John F. Kennedy once championed a future of abundance through projects like NAWAPA, his nephew helped lock a vast region of upstate New York in regulatory stasis to avoid having to build infrastructure.

The consequences are now plain. A region rich in forests, rivers, lakes, and talent has been economically throttled under the guise of environmental stewardship. The Catskills’ water helped build one of the world’s greatest cities, but the city refused to build with the region. The cost? Over a century of missed opportunity, outmigration, and cultural loss, mirroring the struggles of many rural communities that proposals like NAWAPA could have helped.

The water is still here. The people are still here. All we lack is the political will to build again.