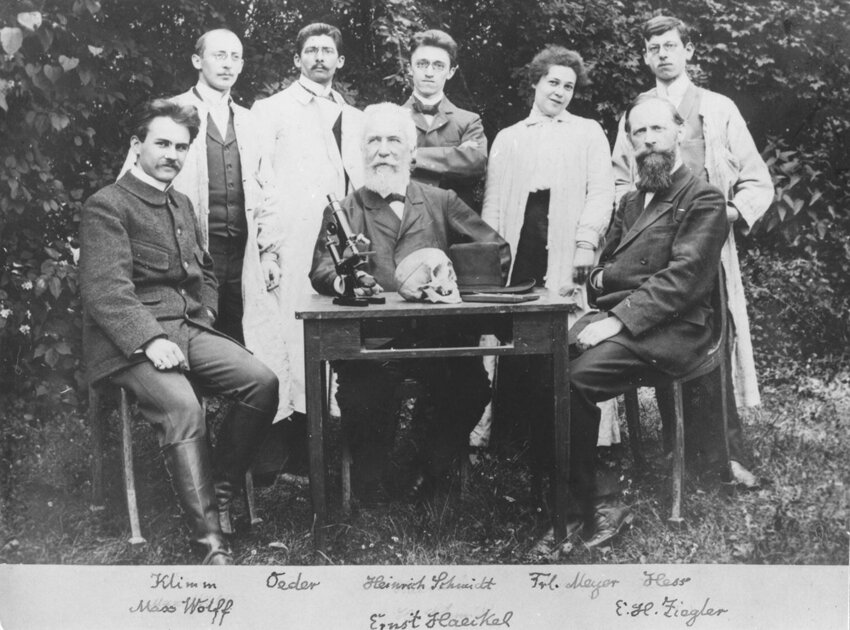

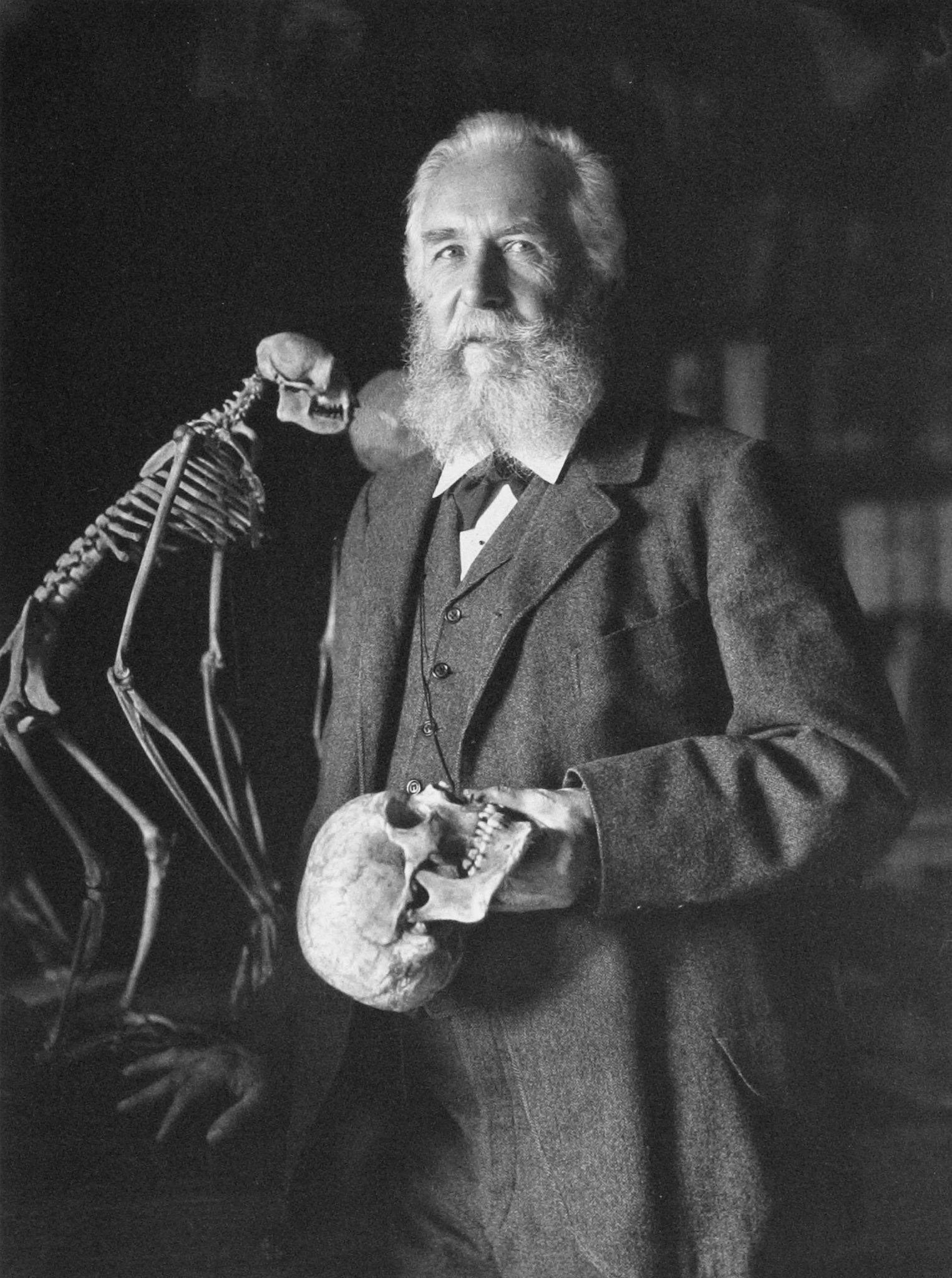

Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) is a name you may or may not be familiar with. If you are, it might be because you’ve seen his botanical art, popular with bohemian Etsy shoppers. And in fact, Haeckel’s biological artwork did inspire the art nouveau movement of the 1920s. His scientific drawings became blueprints for ornate chandeliers, monuments, vases and other ephemera that mimics the beauty of nature. Ironically, though Haeckel’s sketches were of life forms, they have an eerie lifelessness, or even otherworldly quality to them.

Haeckel is also famous for coining the term ‘ecology.’ So much of our current society revolves around this term that it may be hard, in the modern context, to imagine the world before it. But the term ‘ecology’ is relatively new. Ernst Haeckel lived from 1834 to 1919 and first came up with the term ‘oekologie’ in 1866. It took another four decades after Haeckel’s death, for ‘ecology’ to be taken seriously in the scientific community, and even longer for it to become the household concern it is today. Ecology in its early years was sometimes decried as not a science at all but merely a point of view.1

In the wake of widespread recognition, in the 1960s, of the “environmental crisis,” ecology was abruptly thrust into the public arena and widely hailed as an appropriate guide to the relation of humans, as well as other forms of life, to their environment. Strikingly, ecology became a watchword, even in high political circles, just when Paul B. Sears, one of its most articulate practitioners and expositors, described ecology as “a subversive subject” (Sears 1964). Sears’s point was that the view of nature derived from ecological studies called into question some of the cultural and economic premises widely accepted by Western societies. Chief among these premises was that human civilizations, particularly of advanced technological cultures, were above or outside the limitations, or “laws,” of nature (Dunlap 1980b).2

From the beginning, ecology was not limited to a purely scientific notation, it had clear philosophical and epistemological ramifications. It was not just a neutral science; baked into ‘ecology’ was a new theological outlook on humanity and our context within the universe. It questioned previous philosophical axioms underpinning Western civilization itself.

By ecology, we mean the whole science of the relations of the organism to the environment including, in the broad sense, all the “conditions of existence”. Thus, the theory of evolution explains the housekeeping relations of organisms mechanistically as the necessary consequences of effectual causes; and so forms the monistic groundwork of ecology.

Ernst Haeckel (1866)

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution laid the groundwork for Haeckel’s ecology, which was more religion than science, as we now conceive it. Upon examination it becomes clear that the life work of Ernst Haeckel was not merely bohemian paintings, or contributions to the world of scientific thought, but a pilgrimage to undo the humanistic tradition guiding the progress of Western civilization and revert it back to a pseudoscientific, occult pagan dark age. The clearest product of Haeckel’s religious revolution was the National Socialist project of Nazi Germany.

Bending the Rules of Morality in the Name of Science

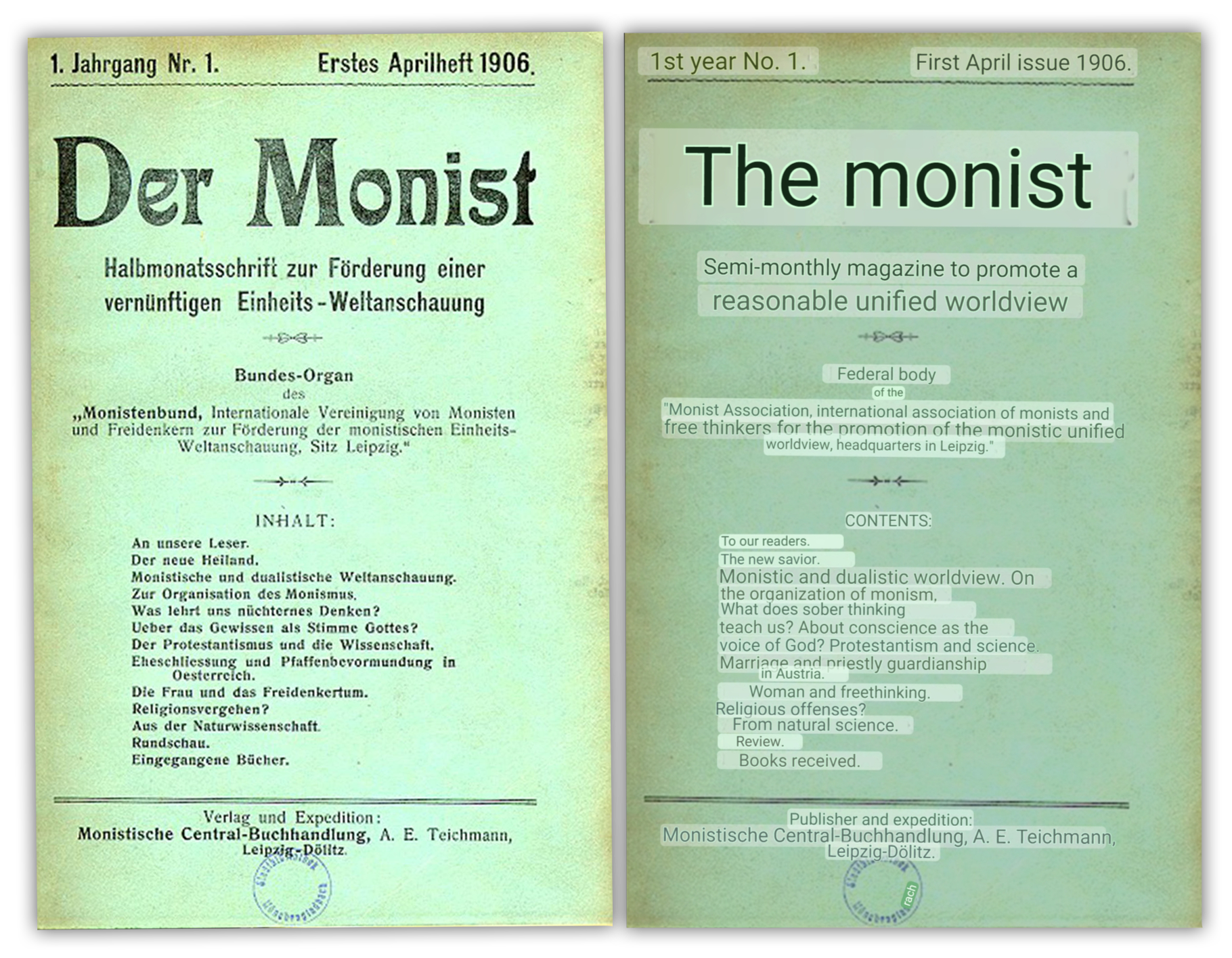

In 1906 Ernst Haeckel founded the Monist League in Jena, Germany, a club meant to capture the imagination of young scientific and technologically minded people. Haeckel’s Monism was a blend of heavy Darwinism and a spiritual outlook that took advantage of the ‘crisis of reason’ pervading the intelligentsia of the mid 1800s.3

Haeckel’s evolutionary Monism was formulated as early as the 1860s, and soon achieved great popularity as the authoritative voice of modern science. Monism’s influence extended not only to the biological and anthropological sciences, but also to a host of ideologies and social movements whose philosophy depended upon an ostensible scientific mandate for determining their ideas and agendas. Many of these movements were progressive, left-liberal, and Marxist but, at the same time, somewhat paradoxically, mystically oriented individuals and groups also fell under the sway of Monism, such as proponents of völkisch nationalism in Germany who desired to create a new kind of nationalist consensus by synthesizing romantic, racial, and scientific beliefs, and adepts of spiritualized nationalism in Italy—adherents of Toscanità—who were also revealingly inspired by the ‘scientific’ maxims of Haeckel’s Monism.4

Despite what current societal maxims may declare, moral foundations precede and therefore heavily inform the art of science. Darwin, Haeckel and the cruel materialist minds of the time represented a new, radical strain in how ‘science’ was conducted. Their epistemological foundations were a major departure from what had come before, and specifically how man was contextualized within the natural world.

Haeckel’s Monism advocated a fundamental and radical departure from the established intellectual and moral traditions of humanistic and rational science, drawing upon alternative heretical and non-Christian traditions of thought that stressed, among other things, the absence of a personal God, the meaninglessness of existence, the essential amorality of the cosmos, and opposition to linear, progressive conceptions of history. His general assumption that the monotheistic God was dead, that mankind was divided into separate and eternally divergent biological races, that the transcendental religions were rooted in anti-scientific superstition, and that morality was historically relative were ideas that came to be accepted among many of the educated and semi-educated classes of Europe as irrefutable truths that were sanctioned by the most up-to-date science. Over time, Haeckel’s notions were increasingly radicalized, and eventually served as a major theoretical basis for National Socialist activity.5

Rerouting the moral framework of society was a trickle-down method to infect the institution of rational science with axioms that eroded not just dignity for human life in general, but specifically, the absolute sanctity of every single individual human life. Instead, thinking of humans as a herd of sheep, or perhaps cells in a larger body, became the norm. With this moral framework, one can see how culling off the ‘useless’ members, as if they were a cancer on the body, becomes the next logical step.

A New View of Mankind and His Relationship to Nature

Haeckel was rabidly anti-Christian. But ‘true atheism’ (or amorality) is not possible for the human mind. We are built to have a spiritual, moral and philosophical outlook. Christianity, for all of its flaws, has, without doubt, been the moral framework that has progressed Western civilization to its furthest heights. To reject Christianity, root and stem, creates a void where much older, darker and less civilized skeletons begin to creep in.

In denying the existence of a transcendent God and stressing the immanence of spirit within matter, Haeckel intentionally rejected the ethical demands of the conventional revealed religions, and he argued forcefully against the supposition of the uniqueness of man or the prospect of historical progress. According to his Monist philosophy, the political realm operated not in progressive linear stages, but according to the ultimate cyclical destiny of the cosmos, and therefore society could not be organized in any other way than as blindly adhering to the morally indifferent laws of nature. To subvert nature and its amoral rules would inevitably and fatally weaken mankind and lead to its racial and physical demise—an accusation that he leveled at Christianity with its roots in ethically imbued Judaism and the Mosaic code. Political life for Haeckel meant simply carrying out the will of nature, and he argued indefatigably on behalf of the idea that politics had to be understood as applied biology—an idea that would, in time, become one of the cardinal theoretical political principles of National Socialism.6

The moral void Haeckel was creating, very much on purpose, by undermining the merits of Christianity, made room for a new dark religious outlook to take hold. This outlook was (and still is) branded to appeal as new and cutting edge to the modern professional class. In a dastardly sleight of hand, what was sold as progressive and new, and not clouded with ‘stuffy old religious ways,’ was actually harkening back to darker religious outlooks; ones that should have remained in the dustbin of history. The poisoned mind-pill was slipped to the young shapers of society – the professional class – without them even realizing, leading to the most dire consequences of the 20th century.

Haeckel’s advocacy of a religion of Monism was intended as a substitute for conventional religion, and his new secular-religious creed achieved surprising popularity among substantial numbers of the educated elite of European society, especially among the ranks of the cultural avant-garde, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These newly formulated scientific-religious ideas also influenced broad strata of the population who were intimately tied to the burgeoning way of life of technically advanced industrial and urban civilization: scientists, engineers, physicians, pharmacists, and teachers, along with self-educated proletarians who frequently received their smattering of formal education by attending Social Democratic Worker Institutes where the curricula were heavily infused with Monist content. Monism even influenced free-floating members of the so-called Lumpenproletariat like Adolf Hitler who, cast adrift in rapidly growing urban commercial centers, were also searching for an ideology that could make sense of the confusion, alienation, and harshness of modern industrial and social conditions.7

A New Religion

Championing Science as the New Religion – it is easy to see where the current mantra of “Believe Science” found its beginning. It is commonplace to see pop culture scientists and personalities who claim to be atheists, frame Christianity as superstitious, anti-scientific and socially backwards. But how often do these figures take a critical historical look at the foundations of their own moral outlook? Perhaps they think they live outside the context of history, or above human morality.

Haeckel and his Monist followers seldom lost an opportunity to criticize established religion. They viewed Christianity as the principal force in the modern world impeding the victory of science, and they accused established religion in Germany of spiritual decay and political reaction. In the place of the Christianity they continually denounced, the Haeckelian Monists proposed that a new pantheistic religion of nature be created which would, they felt, more adequately serve and express the spiritual and national needs of the Germans.

The main goal of the Monist materialist revolution was to recontextualize man as just another part of a single entity. A religion of nature worship, to replace a monotheistic, intelligent and loving God who made man in his image, capable of intelligent reason, morality and the free will to decide for himself whether he would act on this morality or not, was the Haeckelian Darwinist objective. The human being becomes a cell in a body, a single node in a larger living whole.

This, objectively evil outlook laid the groundwork for the cybernetic-ecology-inspired Gaia Hypothesis which rose in popularity in the latter half of the 20th century, (no-so-coincidentally, in the period after the WW2 Nazi leadership was transferred to strategic positions within the Anglo-American intelligentsia).

Having concluded that nature was alive, Haeckel elevated predominant scientific hypotheses of the nineteenth century, such as the theory of spatial ether and the laws of the conservation of mass and energy, to the level of religious dogma and pantheistic faith. Matter, energy, and ether became for him the emanation of some divine spirit and he taught his followers to worship them. ‘The Monistic idea of God which alone is compatible with our present knowledge of nature, recognizes the divine spirit in all things.’ ‘God is everywhere.’ ‘Every atom is animated, and so is the ether.’ Thus, Haeckel presented the universe to his followers as a ‘colossal organism’ bound together by a ‘mobile cosmic ether’ which by its universal diffusion ‘created divinity’ and linked each individual to the divine cosmos. ‘Ever more irresistibly is it borne in upon us that even the human soul is but an insignificant part of the all-embracing “world-soul,” just as the human body is only a small fraction of the great organized physical world.8

It is clear to see Haeckel’s influence on a specific modern liberal stereotype that considers itself ‘above’ religion, only ‘believing in science’ (despite the fact that this phrase is nonsensical; science is the exercise of creative hypothesis informed by contextual information and then proven to have merit, or proximity to truth, through rigorous testing, and even then, is never considered an absolute truth). The word ‘belief’ belies the religious underpinning of current mainstream liberal ethos that dominates our Western institutions. But most well-educated professionals have no idea about the rotten religious, or theosophical roots of the moral framework that guides their ‘hyper-rational’ and ‘purely scientific’ policy work.

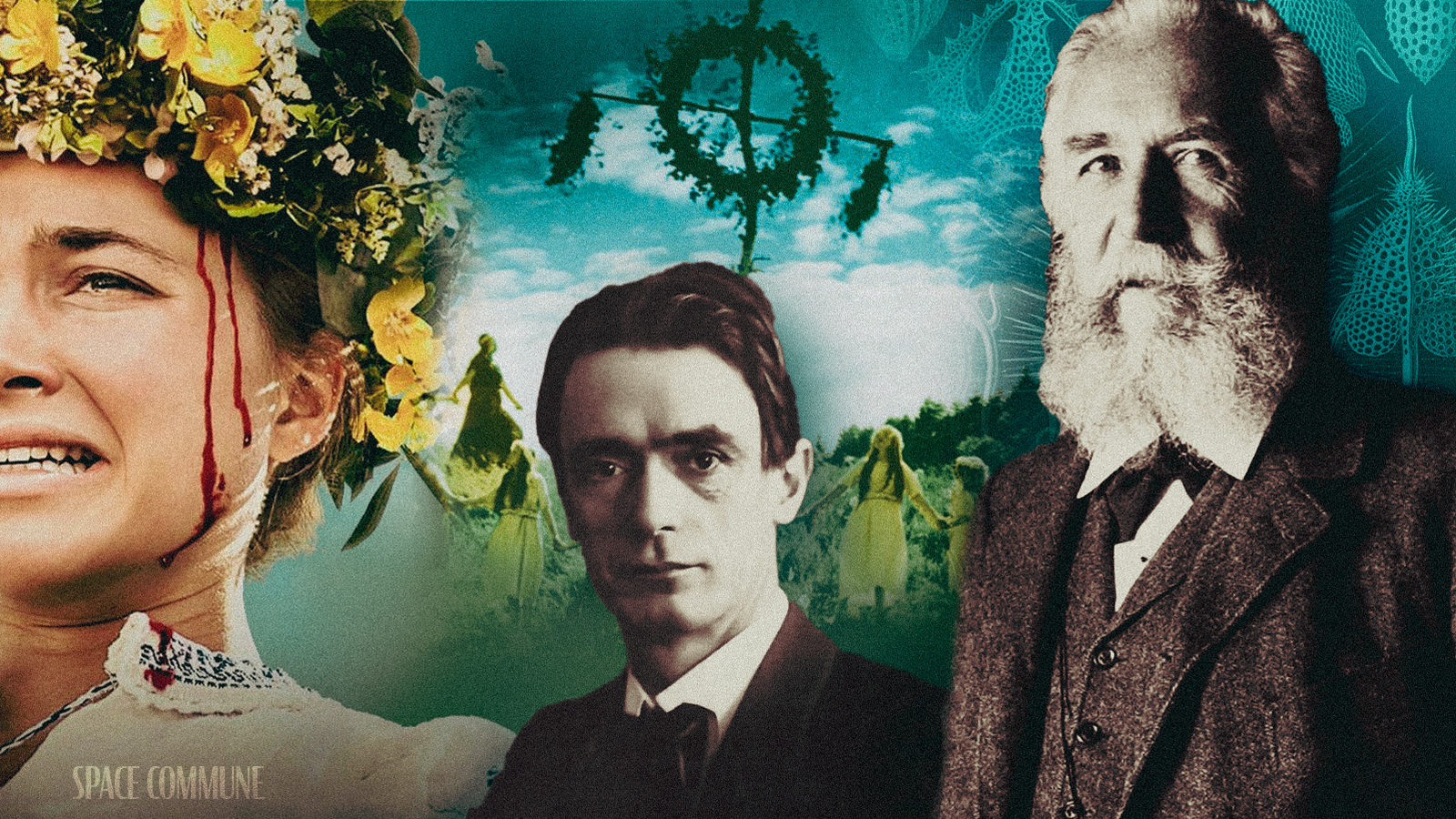

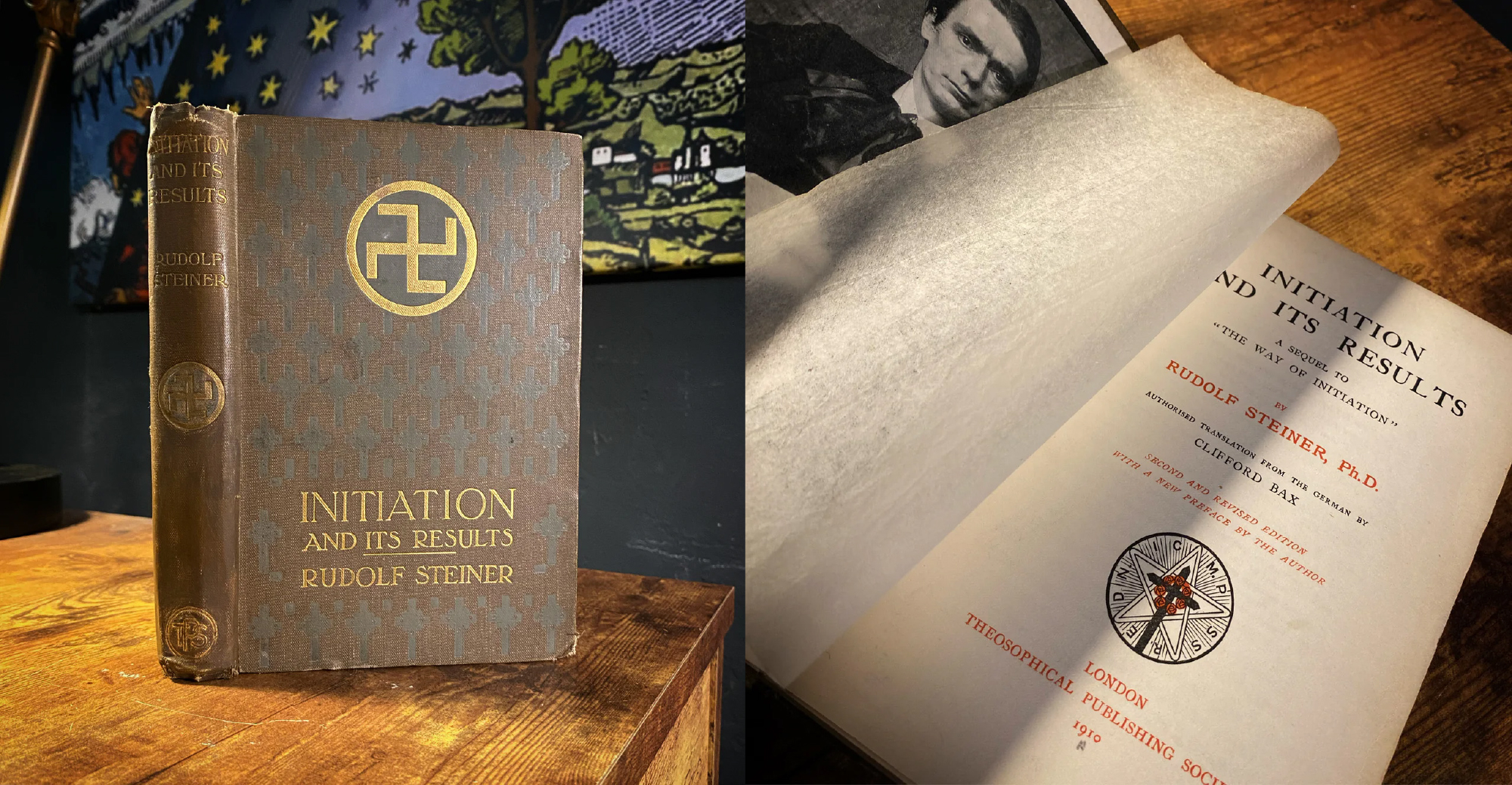

Rudolf Steiner: From Theosophy to Anthroposophy

Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) was an Austrian esotericist, proclaimed clairvoyant, and leader in the Theosophical movement founded by Helena Blavatsky. Steiner later broke with Theosophy, starting his own occult religion called Anthroposophy, grafting together ideas from German idealist philosophy, Theosophy and Christian gnosticism. He founded Waldorf Education and biodynamic agriculture, two institutions with a small, but powerful influence on our world today. Steiner had great admiration for and was inspired deeply by Ernst Haeckel.

Haeckel’s description of the soul quality of nature sounded completely theosophical. In fact, Haeckel was one of the major intellectual mentors of Germany’s leading theosophist, Rudolf Steiner. In the 1890’s both Steiner and Haeckel corresponded with one another and both wrote that they shared a common basic outlook on the nature of the world.9

Steiner, as a spiritual figure, was able to inject Haeckelian Monism and pagan nature worship into the zeitgeist in order to replace humanist Christianity at an institutional level to the same demographic targeted by Haeckel and the rest of the Darwinist cabal.

In addition, around the turn of the twentieth century, important branches of theosophy such as the anthroposophical movement of Rudolf Steiner also consciously and enthusiastically became linked to Ernst Haeckel and to the German Monist League. Theosophy helped to inculcate a general inclination for mysticism in European intellectual life, thus aiding in the creation of the general antirational zeitgeist that contributed to the ‘crisis of reason’ pervading the intellectual environment of the end the 19th century, and in turn helped nourish the birth and development of National Socialist-like ideas.10

But Rudolf Steiner does not just live in the history books. His shadow lurks quite large in our modern society, though most would never know it.

Steiner’s Influence on Modern Society

In 2019 a disturbing hipster horror film called ‘Midsommar’ was released by the posh film company A24. The film revolves around a young woman who has just lost her entire family, mom, dad and sister in a horrific murder-suicide event. In her bereaved state, a friend convinces her, along with a few others in their social group, to take a trip to his homeland in Sweden for a festival. While there, she is fed psychedelics, then proceeds to watch, helplessly, as this back-to-the-land cult first performs suicide rituals among their own people, and then her friends, one by one, start to disappear. At the end of the film, we find out that she has been chosen to join the cult (in some kind of fresh blood, fertility ritual) while it is revealed that all of her friends have been ritualistically murdered, the last, her ex-boyfriend, burned alive in a grass hut as she watches. Writer and director Ari Aster said he took inspiration from Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy to create the film.

Midsommar is not the first film to revolve around pagan cult rituals. The Wicker Man, both the original 1973 version and 2006 Nicholas Cage version had similar themes of pagan cult rituals and human sacrifice culminating in humans being burned alive. But we can go even further back in film history. In 1936 Alfred Rosenberg of the Militant League for German Culture commissioned a film titled Ewiger Wald (or Enchanted Forest in English). Rosenberg, a high ranking Nazi famous for his deep hatred towards Christianity, made sure the film featured pagan rituals, sweeping shots of trees, the forest pictured as a holy temple and of course the maypole festival. The villains of the film were shown to be chopping down sacred forest trees for war and industry, specifically black soldiers brought into Germany by the French occupation army.

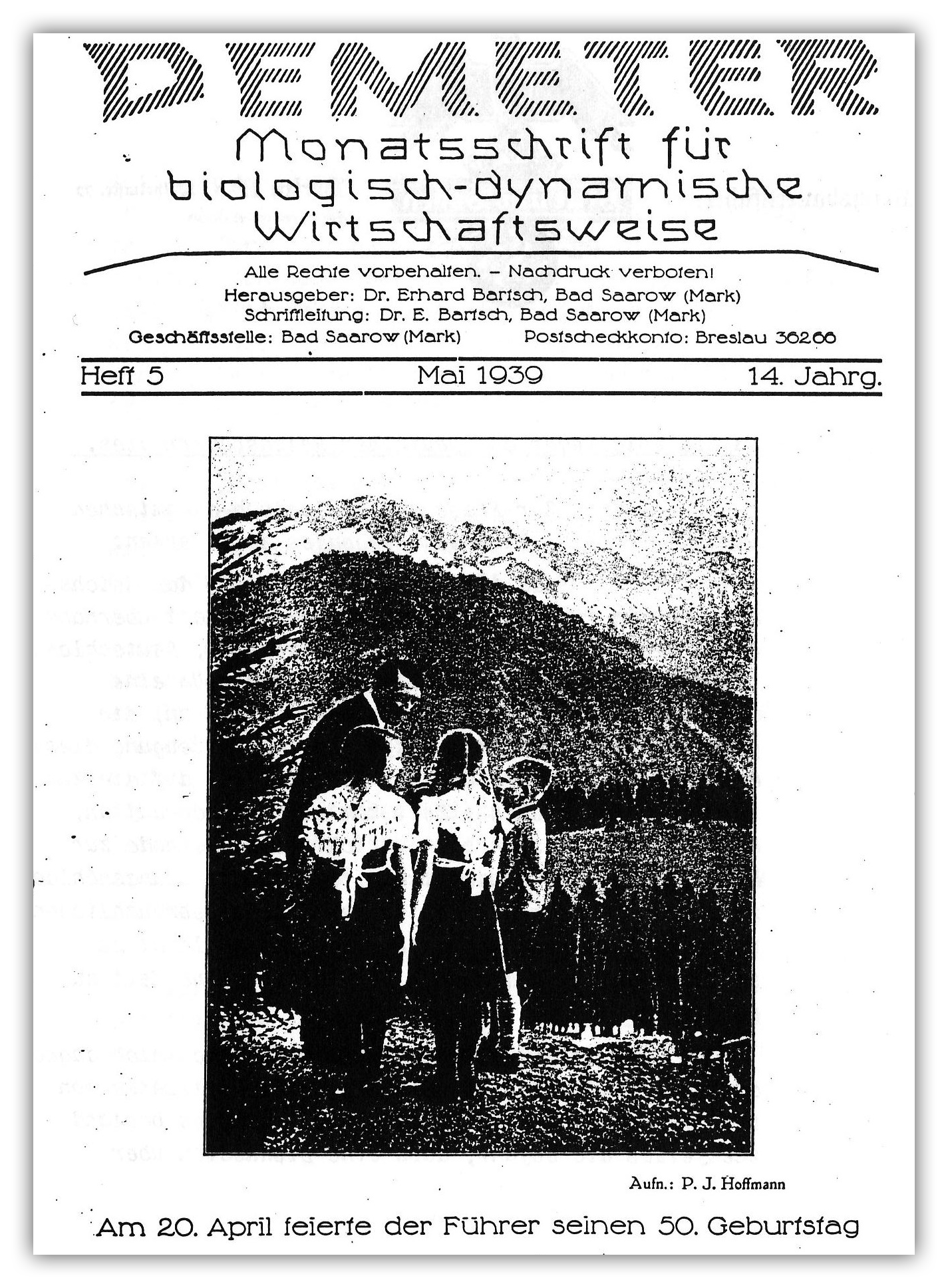

Steiner’s anthroposophy was very popular amongst a large cohort of the Nazi top brass, and the anthroposophic institutions welcomed the admiration as long as it lasted. In 1939, Demeter, the official monthly magazine for biodynamic farming, featured Hitler directly on their cover in celebration of his 50th birthday. Demeter, started in 1924, is still around today, and continues to have an oddly warm and cozy relationship with Nazi iconography. In 2022 their promotional materials, including a monthly calendar, featured a crop circle cut in the shape of a sonnenrad (or black sun); an icon famously associated with Nazi Germany.

Waldorf schools also began with Rudolf Steiner. Most people see them as harmless, alternative education that focuses on creativity; they don’t usually hear about superstitions around ‘milk-teeth’ or belief in gnomes. Nor do they know that the head of NATO, Jens Stoltenberg attended the Oslo Rudolf Steiner School from 1966 to 1975. “When the media asked me what the Waldorf School did for me, I answered: It encouraged me to always strive to become a better human being,” claims Stoltenberg. For those who are unaware, NATO was an employment program for former WW2 Nazis. The chart below shows eight examples of Wehrmacht top brass that transitioned to NATO top brass at the close of WW2.

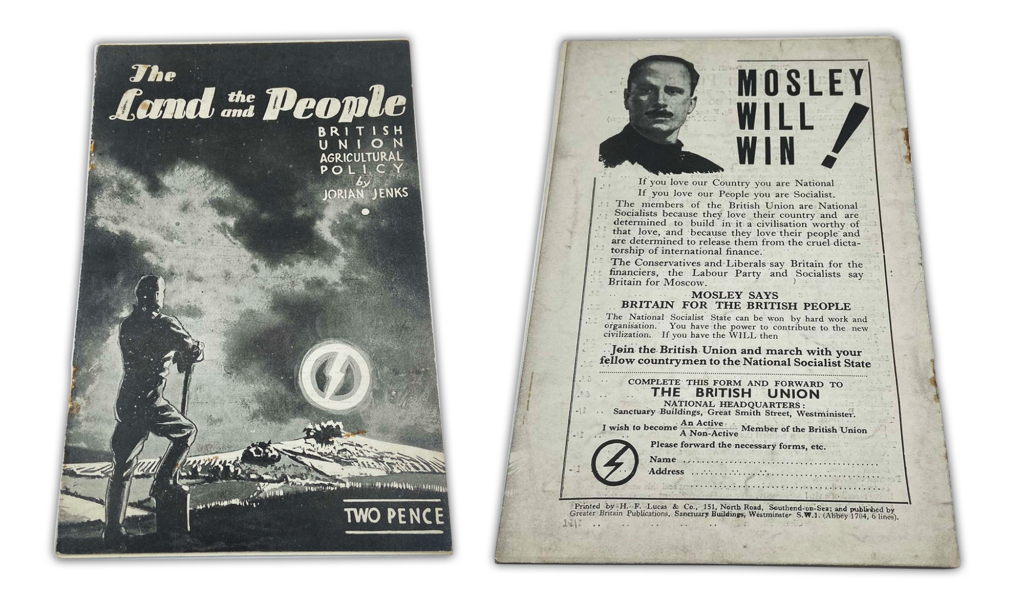

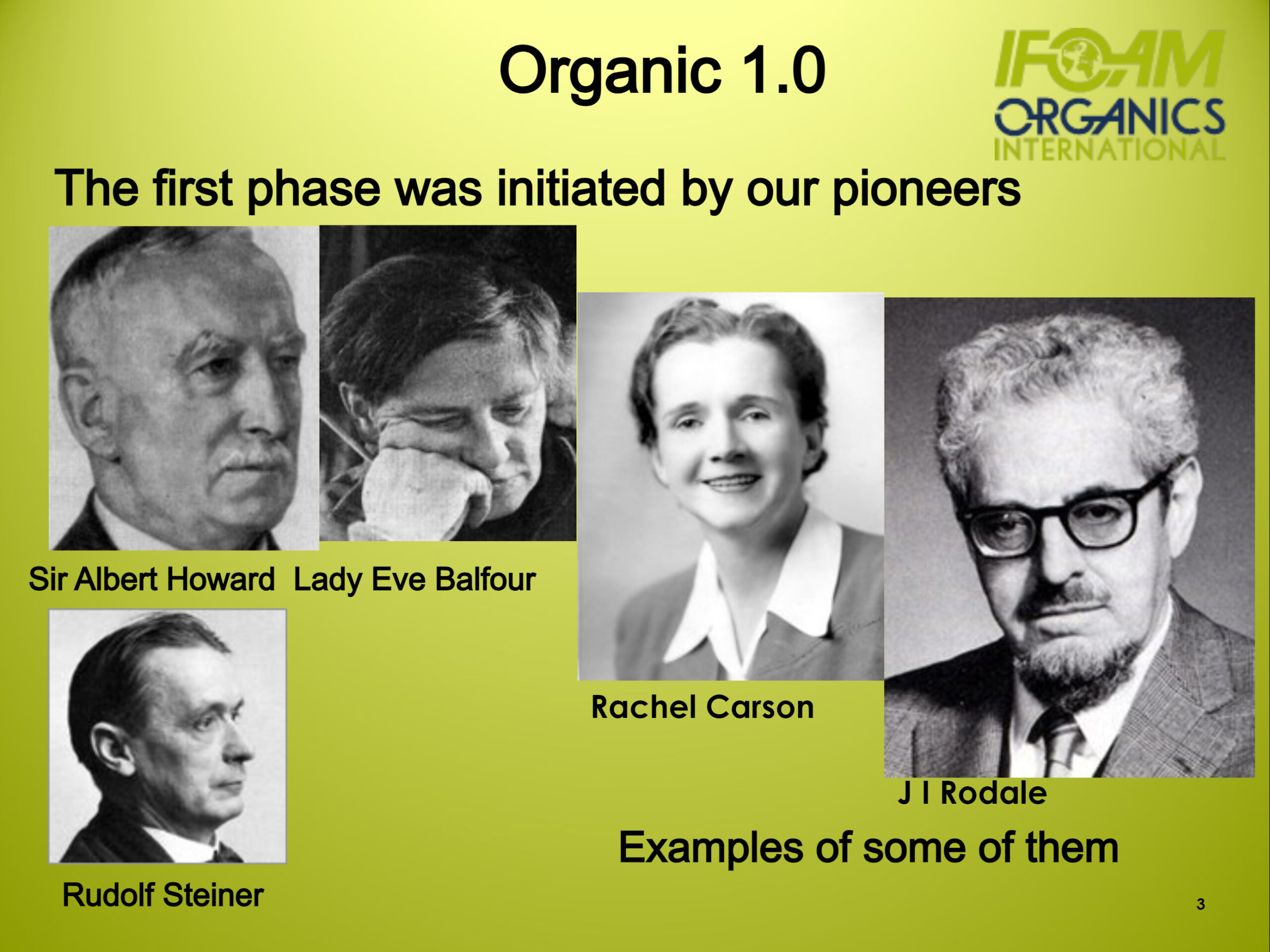

Rudolf Steiner’s influence is felt throughout culture to this day, but the longest lasting legacy of his teachings can be found in the organic food movement. Biodynamic farming, despite always having been a niche, had an outsized influence on the founding of what is today, the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements. Headquartered in Germany, IFOAM was founded in 1972, and is recognized as the global umbrella for organic agriculture, developing standards, guidelines, and certifying bodies for the industry. Key founding members of IFOAM were from the Biodynamic Association as well as Lady Eve Balfour (niece of Lord Balfour) of the Soil Association. The Soil Association was founded by Balfour and Jorian Jenks, among others. Jenks was a close associate with Oswald Mosley, both leading members of the British Union of Fascists. Jenks’ writing was a major influence on Nazi Agriculture Minister Richard Walther Darré who popularized the phrase ‘blood and soil’ in his 1930 book Neuadel aus Blut und Boden (A New Nobility Based On Blood And Soil).

Leftward Turn: The Hippie Movement of the 1960s

The organic food movement had undeniable right-wing beginnings, but after WW2 and Nazism became untenable and rightfully, out of fashion, the movement got a left-wing makeover. By the 1960s, the Soil Association, first founded in 1946, saw new leadership under leftist leaders such as E.F. Schumacher and Barry Commoner.

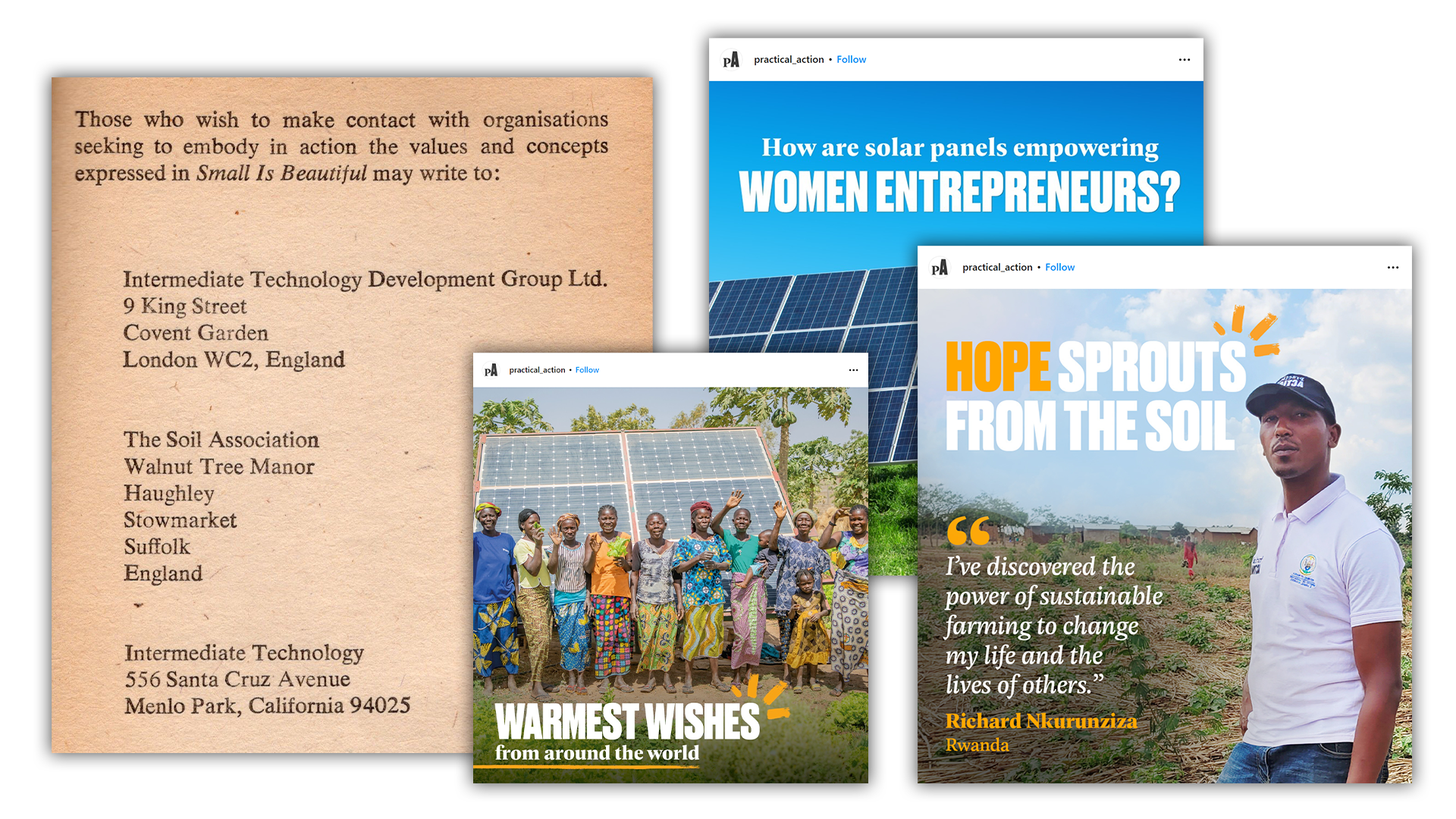

E.F. Schumacher, famous for his Small is Beautiful (1973) book, which preached simple living to comfortably afflicted middle class boomers, had undertones of monastic living and heavy theological underpinnings. It railed against nuclear energy and rallied for “appropriate technologies” for developing nations. In Small is Beautiful, Schumacher adds a few calls-to-action at the conclusion: for more information, the reader can write to: The Soil Association (of course) or the Intermediate Technology Development Group Ltd., an organization founded by Schumacher in 1966, which still exists today under the name Practical Action.

“In the end, intermediate technology will be “labor-intensive” and will lend itself to the use of small scale establishments.” (Small is Beautiful 1973) The plan was to encourage a move away from a technical or ‘hardware’ approach – and towards a ‘development’ approach instead. ITDG changed its name to Practical Action in 2005, building on the previously-held beliefs carried by the organization to focus on pragmatic, holistic and systemic approaches to tackling poverty. We still very much carry Schumacher’s guiding principles with us to this day – using the idea of small is beautiful to inform our work as a global changemaking group.11

Organic farming had been transitioned from right to left wing on the socio-political spectrum. The only difference between left and right wing labor camps, is that the right wing will use brute force, while the left wing will try to convince you it’s in your own best interest.

Barry Commoner (1917-2012), referred to as the “Paul Revere of ecology” by Time Magazine, like Schumacher, was another Keynesian, left-wing leader of the Soil Association. Commoner was an early influencer on what is known today as “eco-socialism”. He wrote many books about environmentalism and energy including The Poverty of Power: Energy and the Economic Crisis (1976). Commoner, like all of the other eco-pundits of his time, bases his entire theory of energy and economics on the Second Law of Thermodynamics; the same law of the conservation of mass and energythat became religious dogma for Haeckel. This simple law was formed by observing how the energy in a closed steam heat engine has a tendency toward entropy over time. This law works perfectly well for small, closed systems. But the clever trick pulled by hucksters like Commoner, since the days of Darwin, has been to extrapolate the entropy law as a foundational law underpinning the entire framework of our universe. In other words, the assertion is that our universe is slowly dying and decaying and will one day die an ultimate heat death. Adopting the 2nd Law as a guidepost for your entire world outlook is concurrent with the Monistic outlook of nature worship; if the entire universe is a single organism, the logic follows that the organism will one day die.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics is perhaps our most powerful scientific insight into how nature works. Now that 150 years have elapsed since the law was discovered, it is perhaps time that we should begin using it to govern the ways in which energy is employed.

Barry Commoner, Poverty of Power: Energy and the Economic Crisis (1976)

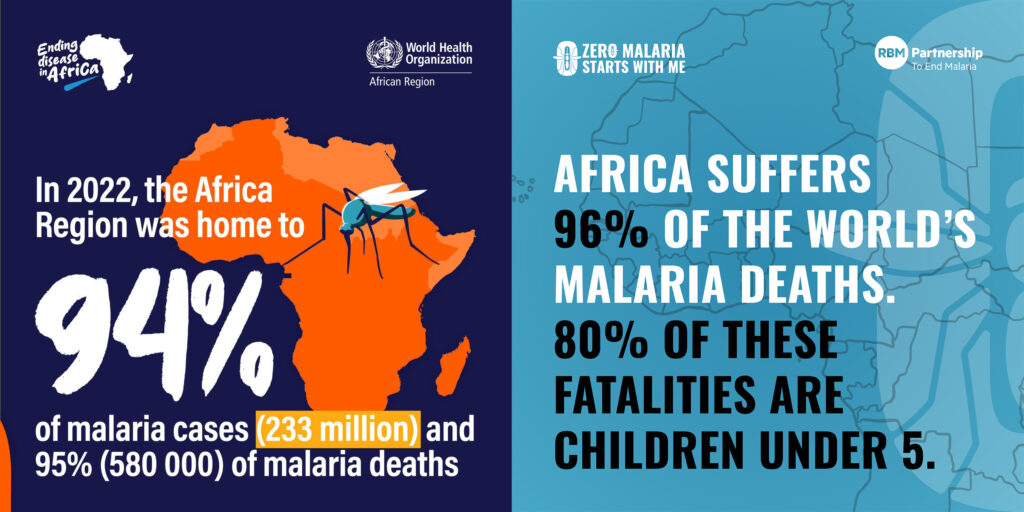

A third, and extremely influential person who emerged from the 20th century ecology movement was Rachel Carson. Some have compared her to Hitler, even saying she has more deaths on her hands due to the fact that she started a worldwide revolution to ban DDT, a chemical used to eliminate malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Mosquitoes are the deadliest animal in the world. They cause, by far, more human deaths (around 1 million per year) than any other animal on the planet. Africa, the same continent that Schumacher’s ITDG ensures will only have “appropriate technologies” is also where the vast majority of Malaria deaths occur.

The campaign against mosquito-killing DDT was effective, due in large to a book, now one of the most famous in the environmental movement, called Silent Spring written by Carson in 1962. Carson’s book is said to have been the catalyst for getting DDT banned in the U.S. and most other nations. But Carson did not pull the hysteria against DDT out of thin air – she had been influenced by a close associate, named Marjorie Spock. Spock had filed a lawsuit against the United States Government for spraying DDT because it interfered with the biodynamic farming she had been doing on her property. Marjorie Spock was, in fact, a member of the Anthroposophical Society who worked directly under Rudolf Steiner. It was her (unsuccessful) lawsuit that provided the framework for the environmentalist blockbuster, the book that has cost millions upon millions of Malaria deaths, Silent Spring.

Humanity is Good

Organic farming is touted as many things: more humane, more balanced with nature, or even simply a way to fight tyranny and become more self-sufficient. Some of these arguments are based on naive economics, or poor understanding of how society is built on energy – with energy density being the key factor in human flourishing. But all of these arguments can be traced back to the same philosophical and theological underpinnings: that human beings are animals, no more or less; that it is alright to sacrifice or cull the weak, and that 2000 years of human-centered approach taught by Christianity must be rolled back to a pagan existence that treats every single individual human life as anything but sacred. The influence of Haecklian Monism and Steinerite cult practices must not be underestimated. It is of utmost importance to understand the source of rot in our current Western society, if we want to revive it. You don’t have to be a devout Christian to understand the importance of a human-centered approach to a healthy society, but we must recognize its philosophical importance if we are to right this ship.

Space Commune is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

- McIntosh, Robert P. The background of ecology, Concept and theory Cambridge University Press 1985

- Ibid

- Gasman, Daniel The Scientific Origins of National Socialism: Social Darwinism in Ernst Haeckel and the German Monist League American Elsevier, 1971

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Practical Action Website, 2021, The roots of our ethos – big change starts small

https://practicalaction.org/news-media/2021/06/30/e-f-schumachers-founding-philosophy-and-how-it-still-guides-us-today/